A microscopic view of a dirty windowsill can reveal some of nature’s smallest wonders.

A meticulously captured image of a rice weevil spreading its wings on a grain of rice secured the top prize in the 2025 Nikon Small World photomicrography competition. Zhang You, an entomologist from China, fortuitously discovered the deceased insect during household cleaning. He immortalized the weevil’s posture by combining over 100 high-resolution microscope photographs.

The rice weevil (Sitophilus oryzae) is notorious for consuming grains and seeds. You has encountered rice infestations previously, but this chance encounter with a lifeless beetle displaying its wings was uncommon. “Since their tiny size complicates the manual preparation of spread-wing specimens, this naturally preserved specimen is a rarity,” remarks You.

He positioned the weevil on a grain of rice to accentuate its diminutive scale. As a first-time winner, You aspires for the image to shed light on the pest’s anatomy. “To me, an exceptional piece blends artistic creativity with scientific precision, capturing the essence and vigor of these organisms,” he states.

The rice weevil is one of 71 impressive images honored on October 15 in this year’s contest. Below are several other standout selections.

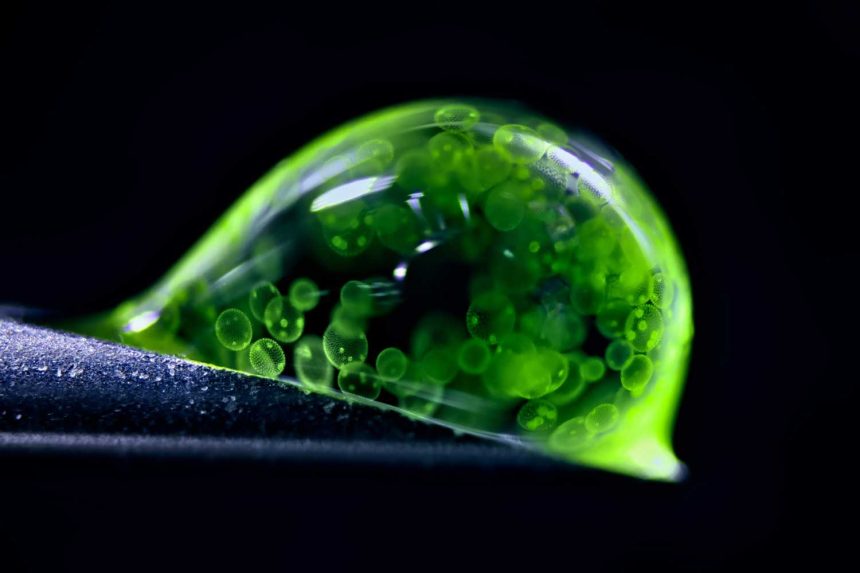

A droplet brimming with life

This clear orb is teeming with a miniature ecosystem.

German photographer and chemist Jan Rosenboom captured hundreds of algae cells swimming through a singular water droplet using a 50-year-old microscope he acquired when he was just 14 years old, utilizing LED lights to illuminate the image.

The algae species Volvox flourishes in freshwater environments such as ponds and puddles. Oval-shaped cells appear in green, while vibrant green dots indicate the formation of the next generation within each parent cell.

Positioned at an exquisite angle on a syringe tip, the droplet showcases scale and optimal lighting. Rosenboom recounted spilling over 20 droplets before managing to take the second-place photograph.

Highlighting the life present in a single droplet of water may foster understanding that even the smallest ecosystems have significant biodiversity deserving of conservation, Rosenboom explains.

Fluorescent ferns

Anatomist Igor Siwanowicz portrayed a vibrant cross-section of fern spores.

Spores function as reproductive units similar to seeds, disseminated by wind or small animals. This fifth-place image, illuminated by fluorescent lasers via a confocal microscope, features three podlike structures called sporangia, which house and develop the spores. The left pod exhibits spores with a brainlike structure; the center pod is unopened, while the right pod, seemingly empty, likely ruptured and released its spores during image preparation, states Siwanowicz. The orange frond tissue of the fern (Ceratopteris richardii) provides a striking backdrop.

Siwanowicz appreciates the image’s chaotic beauty. “Microscopy images tend to be quite abstract and at times daunting, yet they effectively engage a broader audience in the wonders of biology and nature,” he notes from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Janelia Research Campus in Lansdowne, Virginia. “The confusion can provoke curiosity, prompting individuals to delve deeper and learn more.”

Expansive neurons

Though these neurons may evoke the image of an eye’s iris, their intricate structures serve to enhance touch perception, not vision.

Biophysicist Stella Whittaker, working at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke in Bethesda, Maryland, studies sensory neuron structure. The filamentous, root-like appendages allow us to sense our surroundings, she explains.

This remarkable image features the swirling branches of sensory neurons found in our limbs and spine. Whittaker employed fluorescence and antibodies with a confocal microscope to color the image; pink dots indicate actin, an essential protein for muscle contraction. Blue and green microtubules serve as pathways for transporting cellular organelles. At the center, 10,000 cells congregate.

Investigating these neuron structures will yield insights into neurodegenerative diseases such as ALS and Alzheimer’s that target microtubules, Whittaker, currently pursuing a Ph.D. at Weill Cornell School of Medicine in New York City, concludes.

Sunflower hairs

While many people place sunflowers in water, Marek Miś, a photographer and dedicated naturalist in Poland, opted to examine slices of their bristly tissue under a microscope.

These skeletal protrusions are trichomes—tiny hair-like structures that defend sunflowers against pests. Miś extracted the trichomes from a sunflower stem and illuminated the samples with light filtered through a custom polarizing device, a microscopy technique altering lighting orientation and resulting in varied color reflections. The breathtaking magentas and blues in this finalized image, which comprises over 100 composite photographs, reveal the diverse shapes and sizes of trichomes.

“This photograph highlights the diversity of trichomes,” Miś asserts. “The sunflower itself is a beautiful plant, yet it conceals additional beauty invisible to the naked eye.”

Tiny intestines

This depiction of a mouse colon adds sophistication to the gastrointestinal tract.

Biologist Marius Mählen and his research team strive to comprehend tissue growth. “Understanding the principles of healthy tissue formation will illuminate why cancer tumors develop unevenly,” states Mählen from the Friedrich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research in Basel, Switzerland. His group investigates both mouse-derived and stem cell-grown organelles to discern how conditions like colon cancer and inflammatory bowel disease may arise.

Over one weekend, the team captured 600 images of a single mouse colon utilizing a confocal microscope, later stitching the photos together to create a comprehensive image. By employing antibodies and dyes, Mählen’s team marked cells in varying colors: cell nuclei appear white, while membranes are red; a white cluster on the left indicates a group of immune cells vigilant against invaders.