Late one night in 1989, economist Jeffrey Sachs found himself in a smoke-filled room of government officials in Warsaw, Poland. The country had just declared independence from the Soviet Union, which had exerted central control over prices of tens of thousands of items, leading to frequent shortages.

Sachs argued to the economists and politicians that Poland needed “shock therapy” with an immediate transition to a free market economy with floating prices.

For millions of Poles, that was a frightening proposition. Prices posted by the command-style government had been easy for ordinary people to see and understand, but the principles of the free market were an abstract theory. It required faith to leap into the unknown world of supply and demand where an unseen force called “the invisible hand” would now regulate prices.

Sachs’ plan was put in motion the next day, and newly unregulated prices of ordinary grocery items immediately spiked, causing anxiety across the country. The Polish finance minister, Leszek Balcerowicz, paced the streets, looking for a glimmer of hope. He decided to concentrate on one thing: the price of eggs.

If the market was working, the higher price of eggs would create incentives for farmers to bring more eggs to market, leading to a fall in prices. Sure enough, in a few days, egg prices began to drop. “That was an important day,” Balcerowicz recounted, a signal that the new free market was working its magic in allocating goods and services in the most cost effective manner.

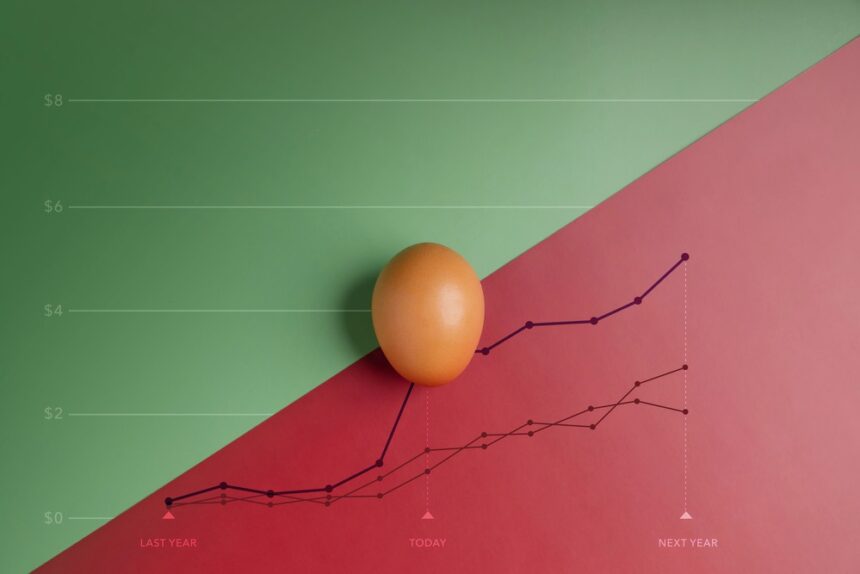

Now, fast forward to 2025 in the United States, where spiking egg prices are dominating news reports. Eggs, like gasoline, are bought frequently, and so tracking these prices is highly relatable to consumers. In fact, 100,000 eggs were stolen from a trailer in early February, and Waffle House even decided to charge a 50 cent surcharge per egg order, making national headlines.

The cost of one dozen Grade A eggs jumped 53 percent higher than the same time last year, with more price volatility due to sudden shocks from bird flu that has killed over 120 million chickens since 2020.

But what’s intriguing is that the egg market is not behaving as expected. Two egg puzzles have emerged that challenge traditional economic theories. Grocery stores are not allowing prices to rise high enough to balance supply and demand, leading to rationing of egg purchases. Additionally, despite rising retail egg prices, stores are actually losing money on each dozen eggs sold.

This deviation from standard economic principles prompts further investigation into the role of government regulations and customer emotions in shaping market dynamics. The emotional aspect of purchasing eggs, coupled with concerns about reputation and customer goodwill, influences grocery stores’ decisions to absorb losses on egg sales and impose sales limits.

Ultimately, the delicate balance between emotion, reputation, and price equilibrium in the egg market highlights the complexities of human behavior in economic transactions. Consumers are shielded from the reality of higher wholesale prices, while grocery stores navigate the fine line between profit maximization and customer satisfaction.

In conclusion, the egg market serves as a microcosm of the broader economic landscape, where competition and consumer protection are essential. The interplay of emotion, reputation, and pricing strategies underscores the importance of market dynamics in ensuring fair and efficient outcomes for all stakeholders.

Craig Richardson is the BB&T Distinguished Professor of Economics and Finance at Winston-Salem State University.