If you’re in need of a break from the chaos of current American politics, the International Center of Photography’s exhibition, “American Job: 1940-2011,” may not be the ideal escape. This powerful showcase delves into the complex history of work in the United States, featuring images captured by more than 40 photographers. These photographs document a wide range of topics including labor organizing, strikes, protests against gender and racial inequality, mass unemployment, the impact of economic restructuring, political campaigns, and the diverse jobs held by individuals across various sectors such as coal mining and domestic labor.

Walking through the exhibition, one can’t help but be moved by the emotional impact of the images on display. For instance, a photograph by Ernest Withers from 1968 showing Black sanitation workers holding signs that read “I Am a Man” elicits a strong emotional response from visitors, as was witnessed by a woman tearing up in front of the image during a recent visit. This serves as a reminder that the struggles depicted in these photographs are not a thing of the past, but rather an ongoing battle that continues to this day.

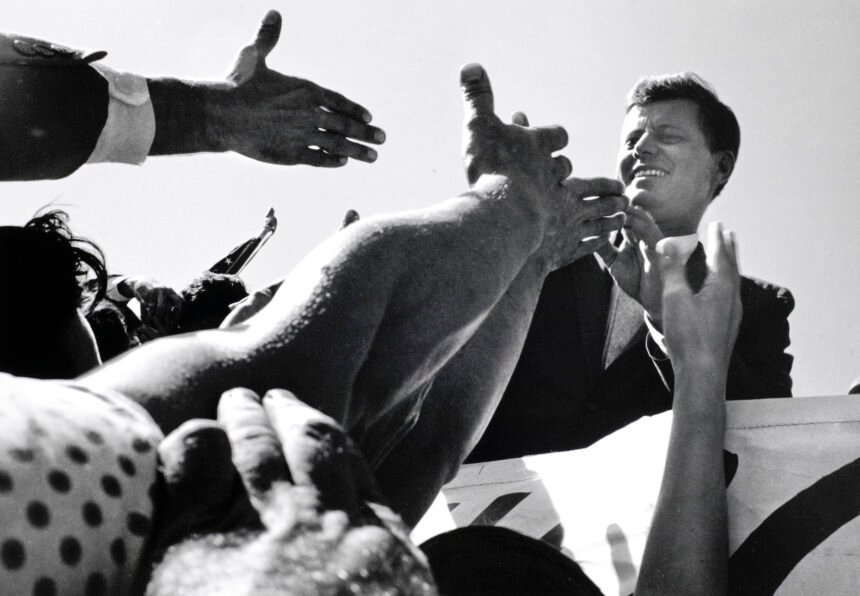

The exhibition is divided into five chronological sections, with one of the central themes being the call to action encapsulated by the words of labor activist Joe Hill: “Don’t mourn, organize!” Many of the images in the show capture individuals and groups actively engaging in this sentiment, whether through political campaigns, labor strikes, or other forms of collective action. Some of the more well-known photographs featured in the exhibition include Cornell Capa’s images of John F. Kennedy’s 1960 presidential campaign and W. Eugene Smith’s 1951 photo essay on Nurse Midwife Maude Callen, whose work caring for impoverished patients in rural South Carolina is poignantly documented.

While some of the photographers behind these images remain anonymous, their work speaks volumes about the power of photography as a tool for social change. The exhibition also sheds light on organizations like the Workers Film and Photo League, which advocated for radical social change through photography and taught photography to working-class New Yorkers. Despite facing suppression and blacklisting due to their leftist politics, the legacy of these organizations lives on through the images they captured.

However, while “American Job” offers a comprehensive visual chronology of the history of work in the United States, it falls short in providing a deeper understanding of the role of photography in shaping these historical moments. The exhibition could benefit from exploring how photography influences the construction of history, the dissemination of images, and the various forms of labor involved in the creation and distribution of photographs. Additionally, the physical presentation of the photographs could be improved to enhance the viewing experience for visitors.

In conclusion, “American Job: 1940-2011” is a thought-provoking exhibition that offers a glimpse into the multifaceted history of work in America. It serves as a reminder of the ongoing struggles for labor rights, social justice, and equality that continue to shape our society. The exhibition runs at the International Center of Photography Museum through May 5th and is curated by Makeda Best.