The vast American prairie has long been a source of wonder and fear for those who have encountered it. Stretching across a quarter of North America, the seemingly endless grasslands have challenged and transformed all who have tried to tame them. Early European settlers faced a daunting task as they attempted to make a home in this alien landscape, leading to a phenomenon known as prairie madness.

Prairie madness, as documented by journalist E.V. Smalley in 1893, described the alarming amount of insanity that occurred among farmers and their wives in the new Prairie States. The isolation, drought, and debt drove many settlers to the brink of despair, causing them to abandon their homesteads and return East. However, those who stayed embarked on a monumental terraforming project that would reshape the land, climate, and future of the continent.

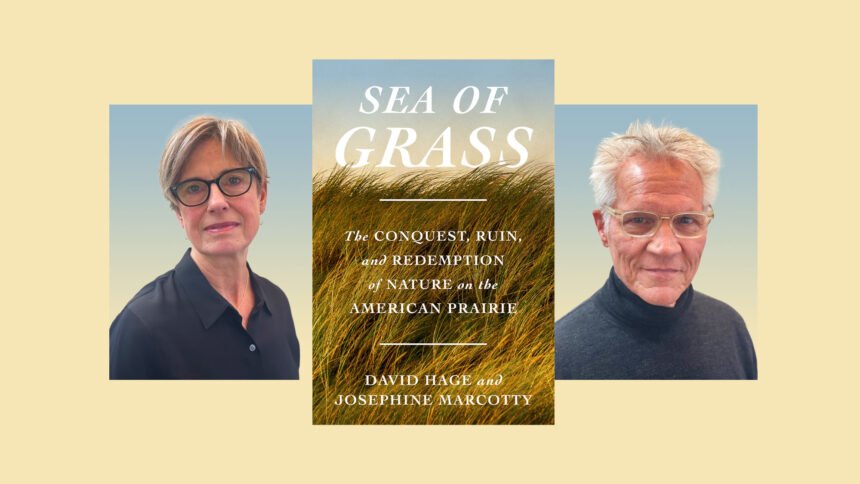

In their book, “Sea of Grass: The Conquest, Ruin, and Redemption of Nature on the American Prairie,” authors Dave Hage and Josephine Marcotty explore this transformation in detail. They highlight how European colonizers in the nineteenth century dramatically altered the continent’s hydrology in less than a hundred years, displacing Indigenous nations and disrupting ancient carbon and nitrogen cycles in the process.

The deep black soil of the Midwest, a result of millennia of plant and animal decomposition, became the foundation of the modern food system. However, this transformation also dismantled one of the Earth’s most effective climate defenses, as the prairie’s grasses played a crucial role in absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Today, the tallgrass prairie, once abundant in states like Illinois, Iowa, and Minnesota, now only covers about 1% of its former range. The authors point out the paradox of the prairie, noting that despite being feared and dismissed as a wasteland, it is actually one of the richest ecosystems on Earth.

Hage and Marcotty emphasize the importance of understanding and caring for the prairie in the face of a rapidly warming climate. They stress the need to restore grasslands to help absorb carbon dioxide and combat climate change. By recognizing the value and significance of the prairie, we can work towards preserving and restoring this unique ecosystem for future generations. But it’s not like they’re getting rich off of it. They’re getting by. So if you’re going to change the way that we incentivize farming, which is what it’s going to take, you’re going to have to provide some other form of income for those farmers. You can’t just pull the rug out from under them. You’re talking about a major restructuring of American agriculture. That’s not going to happen overnight. But it’s becoming increasingly clear that we need to do something different.

JM: One of the things that we write about in the book is that we don’t think that the people who are farming this way are happier. They’re struggling, and they’re struggling to keep their heads above water. So it’s not just the land that’s suffering, it’s the people who are farming it. And the people who are farming it have to be part of the solution. They have to be part of the conversation about how we change this.

DH: It’s a big ask for farmers to voluntarily give up what they’re doing. But if we can figure out a way to make it worth their while, to make it economically feasible, then I think there’s a lot of hope.

In conclusion, the destruction of the prairie has not only had devastating ecological consequences but has also led to the isolation and mental illness of those living in rural areas. It is crucial that we find a way to restore the prairie and support those who rely on it for their livelihoods. By addressing the root causes of prairie destruction and providing alternative economic opportunities for farmers, we can work towards a more sustainable future for both the land and its inhabitants.

The Midwest is a region heavily dependent on agriculture, with many farmers relying on the production of corn for their livelihoods. In recent years, the ethanol mandate has played a significant role in shaping the economics of farming in this region. Farmers have reported that they would not be able to sell their corn crops without the demand for ethanol, and that ethanol has been a key factor in their ability to turn a profit.

Politicians campaigning in the Midwest face a tough challenge when it comes to standing up against ethanol, as the industry has become intertwined with the livelihoods of many farmers in the region. However, the authors of a new book on agriculture argue that it would only take modest changes to the federal farm bill to create a more sustainable and environmentally friendly farming system. By winding down the ethanol mandate and increasing funding for federal conservation programs that reward farmers for adopting conservation practices, it is possible to create a more balanced and sustainable agricultural system.

The authors of the book point out that the current system is driven more by federal policy than by market forces, leading farmers to rely on subsidies that push them towards unsustainable practices such as monoculture farming and heavy chemical use. They argue that a more diverse and complex farming system, with a focus on crop rotation and cover crops, could lead to healthier soil, reduced flooding and erosion, and less reliance on fossil fuel-based inputs.

Research from institutions like Iowa State University and the University of Minnesota supports the idea that a more diverse crop rotation can have a positive impact on soil health and environmental sustainability. By moving towards a more sustainable and diverse farming system, farmers in the Midwest can not only protect their livelihoods but also contribute to the preservation of the prairie ecosystem.

Overall, the authors of the book present an alternative vision for agriculture in the Midwest, one that focuses on sustainability, conservation, and diversity. By making modest changes to federal policy and encouraging farmers to adopt more sustainable practices, it is possible to create a more resilient and environmentally friendly agricultural system in the region.