On June 17, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent tweeted:

Recent reports indicate that stablecoins could burgeon into a $3.7 trillion market by the decade’s end. This scenario gains traction with the passage of the GENIUS Act.

A flourishing stablecoin ecosystem will catalyze private sector demand for US Treasuries, which serve as the backbone for stablecoins. This surge in demand could potentially reduce government borrowing costs and assist in managing the national debt, while simultaneously introducing millions worldwide to the dollar-based digital asset economy.

However, Bessent’s tweet contains a couple of fundamental economic missteps. First, as my former GMU professor Larry White astutely noted, an uptick in demand for Treasury bills would lead to an increase in the equilibrium quantity of these instruments traded in the marketplace. In simpler terms, we would see a rise in the quantity demanded for US government debt, not a decrease.

Secondly, as interest rates decline, so too does the government’s borrowing costs. This follows the basic law of demand: when the price of something drops, the quantity demanded tends to rise. Consequently, if Bessent’s assertion that stablecoins will thrive holds true, we would expect to see a greater appetite for government debt, rather than a reduction.

It’s conceivable that Secretary Bessent stumbled upon my EconLog post from about a year ago, where I discussed:

The decision-makers in spending and budgeting often do not bear the full costs of their choices. Neither do voters, as those costs are distributed across the taxpayer base. This phenomenon leads to a scenario that James Buchanan and Richard Wagner termed “Democracy in Deficit”: politicians favor easy decisions over difficult ones, generally advocating for increased spending and lower taxes.

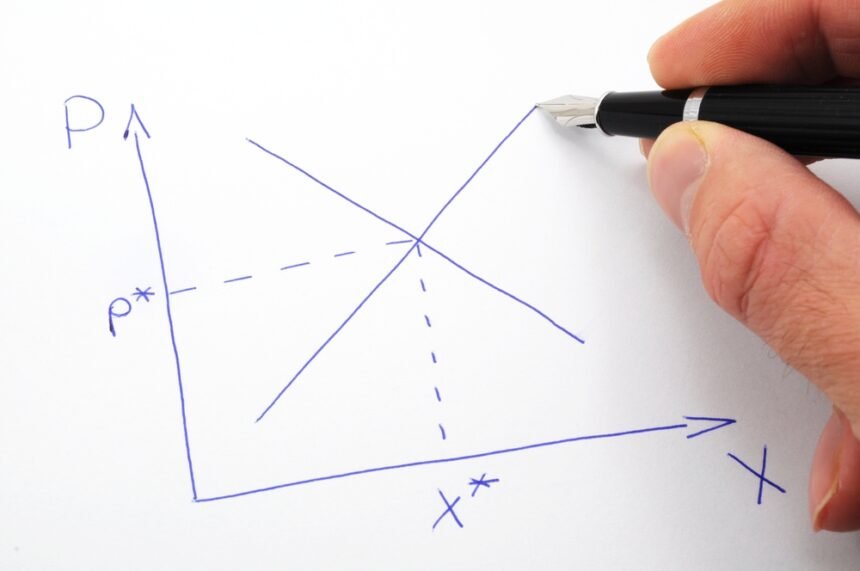

In this context, the supply of Treasury bills remains unaffected by the price level—think of it as a perfectly inelastic supply (a vertical line for those drawing supply and demand graphs at home). Yet, even with this inelasticity, Bessent’s perspective remains flawed. If borrowing levels are independent of price, an increase in demand would lower interest rates but would not alter the volume of debt issued. Thus, claiming that federal debt would be curtailed is misleading.

While it’s theoretically possible for the demand curve for Treasury bills to slope upward (though I can’t fathom why they would resemble a Giffen good), such a scenario seems empirically improbable.

—

*For those less familiar with monetary economics: bond prices and interest rates (or bond yields) move inversely. When bond prices rise, yields fall, and vice versa. The bond’s price is what you pay upfront, while the yield is what the bondholder earns over and above that price at maturity.