Malawi Rock Shelter Reveals Oldest Evidence of Funeral Pyre for an Adult

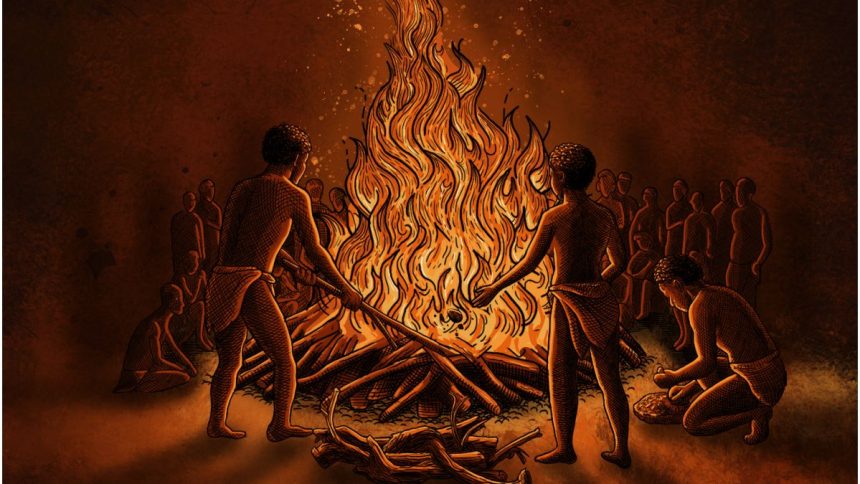

Deep in an ancient rock shelter in Malawi, archaeologists have uncovered the world’s oldest evidence of a funeral pyre for an adult. The charred remains, dating back 9,500 years, belong to a woman aged between 18 and 60 years old. Her body was meticulously prepared for cremation on a large pyre that burned for hours as part of a deliberate funerary ritual.

Anthropologist Jessica Cerezo-Román from the University of Oklahoma leads the team that made this groundbreaking discovery. They describe it as “the earliest evidence for intentional cremation in Africa, the oldest in situ adult pyre in the world.”

Complex Hunter-Gatherer Funerals

This finding challenges previous assumptions about the simplicity of hunter-gatherer funerals. The elaborate ceremony involved careful planning, construction, and a significant investment of resources to gather and maintain the large amount of wood needed for the pyre to burn effectively.

The continuous use of the site suggests a shared social memory and possibly forms of ancestor veneration, which were previously thought to be minimal among mobile foragers.

Historical Significance

The significance of this discovery lies in the long-standing tradition of revering the dead. The earliest intentional burial dates back 78,000 years, highlighting the deep-rooted human instinct to honor the deceased.

While evidence of cremation before 7,000 years ago is scarce, the Malawi rock shelter provides a unique insight into early cremation practices among hunter-gatherer cultures.

Archaeological Significance

The archaeological site at Mount Hora has been active for an estimated 21,000 years, with evidence of mortuary practices dating back 16,000 to 8,000 years. At least 11 individuals have been identified at the site, with only one showing evidence of cremation before burial.

This individual, known as Hora 3, underwent a complex cremation ritual, with her bones exposed to high temperatures for an extended period. Cut marks on the bones indicate disarticulation before cremation, and color patterns suggest movement during the process.

Continued Ritual Practices

The extensive ash deposit at the site suggests the use of at least 30 kilograms of wood, grass, and leaves for the pyre. The presence of ash layers over the remains indicates continued use of the site for fires over several hundred years after the cremation.

Researchers interpret this as evidence of a “persistent place” tied to territory and ancestral connections, highlighting the deep-rooted tradition of memory-making and place-making in hunter-gatherer societies.

The research has been published in Science Advances.