Researchers from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore (NUS Medicine), have made a groundbreaking discovery regarding the spread of a multidrug-resistant strain of Escherichia coli sequence type 131 (E. coli ST131) within households. This strain of E. coli can be carried by individuals in their gut for prolonged periods without causing any symptoms, allowing them to unknowingly pass it on to their family members.

Published in Nature Communications, this study is one of the first in Asia to investigate how this antibiotic-resistant bacterium circulates within the community. E. coli is a common bacterium found in the intestines of humans and animals, with most strains being harmless and even beneficial for gut health. However, certain strains can cause diseases when they acquire specific genes that enable them to produce toxins or invade tissues.

E. coli ST131 is a globally widespread strain that is known for its antibiotic resistance. Unlike other E. coli strains that cause gastrointestinal infections, E. coli ST131 often leads to urinary tract infections and other serious conditions, especially in vulnerable populations. The rise of antibiotic resistance, driven by superbugs like E. coli ST131, is a major concern in both hospital and community settings.

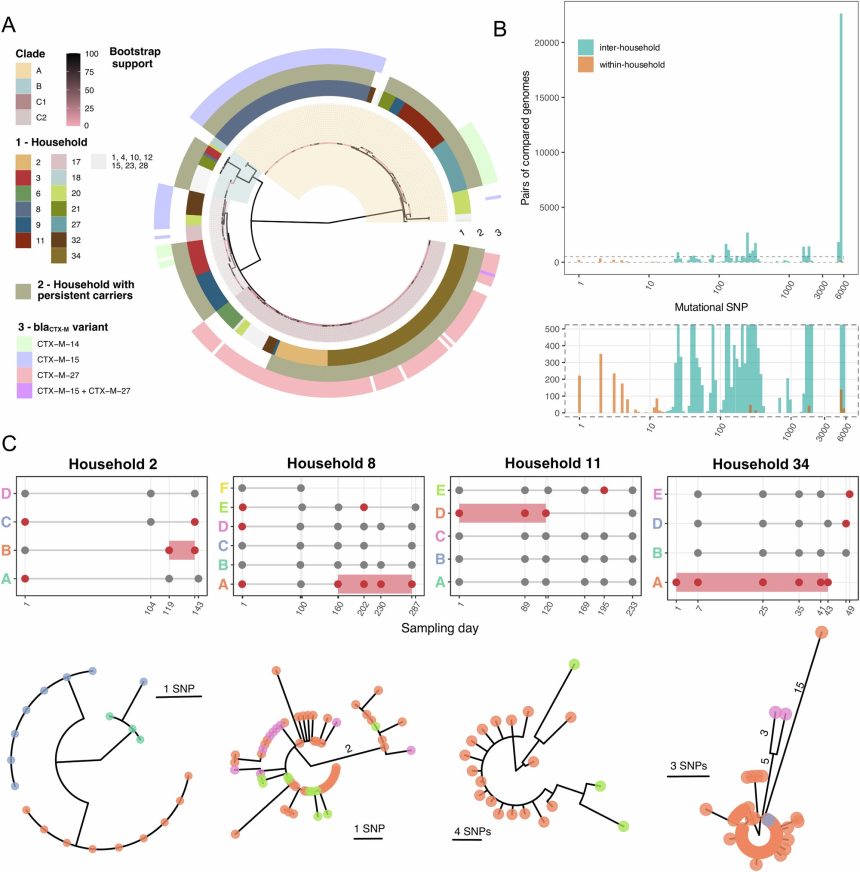

The research team followed 34 families in Singapore, collecting stool samples from 135 participants to test for E. coli, including E. coli ST131. Through genetic sequencing, they identified individuals who carried high levels of the resistant bacteria without showing any symptoms. These “silent carriers” were found to be the source of transmission to their family members, indicating that they may act as hidden reservoirs that sustain the spread of resistant bacteria in the community.

Dr. Mo Yin from the Infectious Diseases Translational Research Program at NUS Medicine, who led the study, emphasized the importance of identifying individuals who carry high levels of resistant bacteria without symptoms. By doing so, targeted prevention strategies can be developed to reduce the risk of community transmission. The study highlights the need for good personal hygiene practices at home and the development of new approaches to reduce long-term carriage of resistant bacteria.

Potential strategies to combat the spread of antibiotic resistance include vaccines, probiotics, prebiotics, or fecal transplants. Targeting interventions at individuals who carry high levels of resistant bacteria could help prevent widespread transmission and the escalation of antibiotic resistance. Professor Paul Tambyah, Deputy Chair of the Infectious Diseases TRP at NUS Medicine, emphasized the importance of understanding how these bacteria persist and move between individuals to develop community-based solutions to contain antibiotic resistance.

The research team plans to further investigate the gut microbiome of participants to understand how the balance between beneficial and harmful bacteria influences the long-term carriage of resistant strains. These findings will contribute to global efforts to combat the rise of antibiotic resistance and protect public health.

In conclusion, this study sheds light on the silent spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria within households and underscores the importance of targeted prevention strategies to curb the transmission of superbugs like E. coli ST131. By identifying and addressing silent carriers, we can take steps towards reducing the risk of community transmission and preserving the effectiveness of antibiotics for future generations.