Embracing Boredom: A Positive Perspective

We have all experienced boredom – that feeling of waning interest or decreased mental stimulation. Eventually we lose focus, we disengage. Time seems to pass slowly, and we may even start to feel restless. Whether it be watching a movie that disappoints, a child complaining that “there’s nothing to do”, or an adult zoning out during a meeting – boredom is a universal experience.

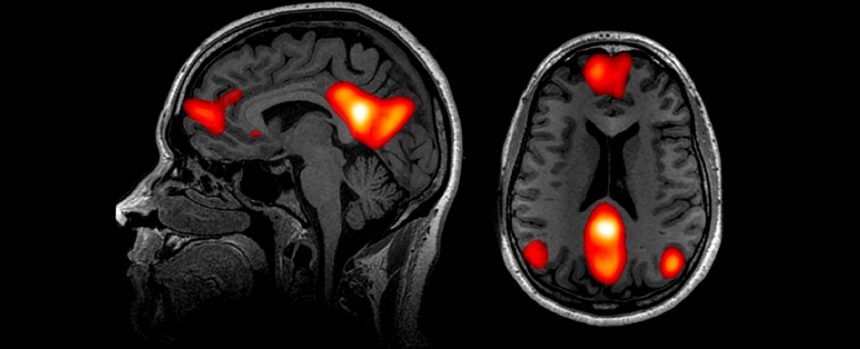

The Brain on Boredom

When we experience boredom – say, while watching a movie – our brain engages specific networks. The attention network prioritises relevant stimuli while filtering out distractions and is active when we commence the movie. However, as our attention wanes, activity in the attention network decreases, reflecting our diminished ability to maintain focus on the unengaging content. Likewise, decreased activity occurs in the frontoparietal or executive control network due to the struggle to maintain engagement with the unengaging movie.

Simultaneously, the default mode network activates, shifting our attention toward internal thoughts and self-reflection. This is a core function of the default mode network, referred to as introspection, and suggestive of a strategy for coping with boredom.

This complex interplay of networks involves several key brain regions “working together” during the state of boredom. The insula is a key hub for sensory and emotional processing. This region shows increased activity when detecting internal body signals – such as thoughts of boredom – indicating the movie is no longer engaging. This is often referred to as “interoception”.

The amygdala can be likened to an internal alarm system. It processes emotional information and plays a role in forming emotional memories. During boredom, this region processes associated negative emotions, and the ventral medial prefrontal cortex motivates us to seek alternative stimulating activities.

Boredom versus Overstimulation

We live in a society that subjects us to information overload and high stress. Relatedly, many of us have adopted a fast-paced lifestyle, constantly scheduling ourselves to keep busy. This constant stimulation can be costly – particularly for our nervous system. Our overscheduling can feed into overstimulation of the nervous system. The sympathetic nervous system, which manages our fight-or-flight response, can stay activated for too long, leading to increased risk of anxiety.

Could Boredom be Good for Us?

In small doses, boredom is the necessary counterbalance to the overstimulated world in which we live. It can offer unique benefits for our nervous system and mental health. There are several benefits of giving ourselves permission to be occasionally bored:

- Improvements in creativity, allowing us to build “flow” in our thoughts

- Development of independence in thinking and encourages finding other interests rather than relying on constant external input

- Supports self-esteem and emotional regulation, because unstructured times can help us sit with our feelings which are important for managing anxiety

- Encourages periods without device use and breaks the loop of instant gratification that contributes to compulsive device use

- Rebalances the nervous system and reduces sensory input to help calm anxiety

Embrace the Pause

Anxiety levels are on the rise worldwide, especially among our youth. Many factors contribute to this trend. We are constantly “on”, striving to ensure we are scheduling for every moment. But in doing so, we are potentially depriving our brains and bodies of the downtime they need to reset and recharge. We need to embrace the pause. It is a space where creativity can prosper, emotions can be regulated, and the nervous system can reset.

Michelle Kennedy, Youth Mental Health Researcher, University of the Sunshine Coast and Daniel Hermens, Professor of Youth Mental Health & Neurobiology, University of the Sunshine Coast

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.