Carla Stellweg, a groundbreaking curator and writer who played a pivotal role in redefining Mexican contemporary art during a crucial period in the nation’s history, passed away on Monday, October 20, at her home in Cuernavaca, Mexico, at the age of 83. Her son, writer George Stellweg, confirmed her death.

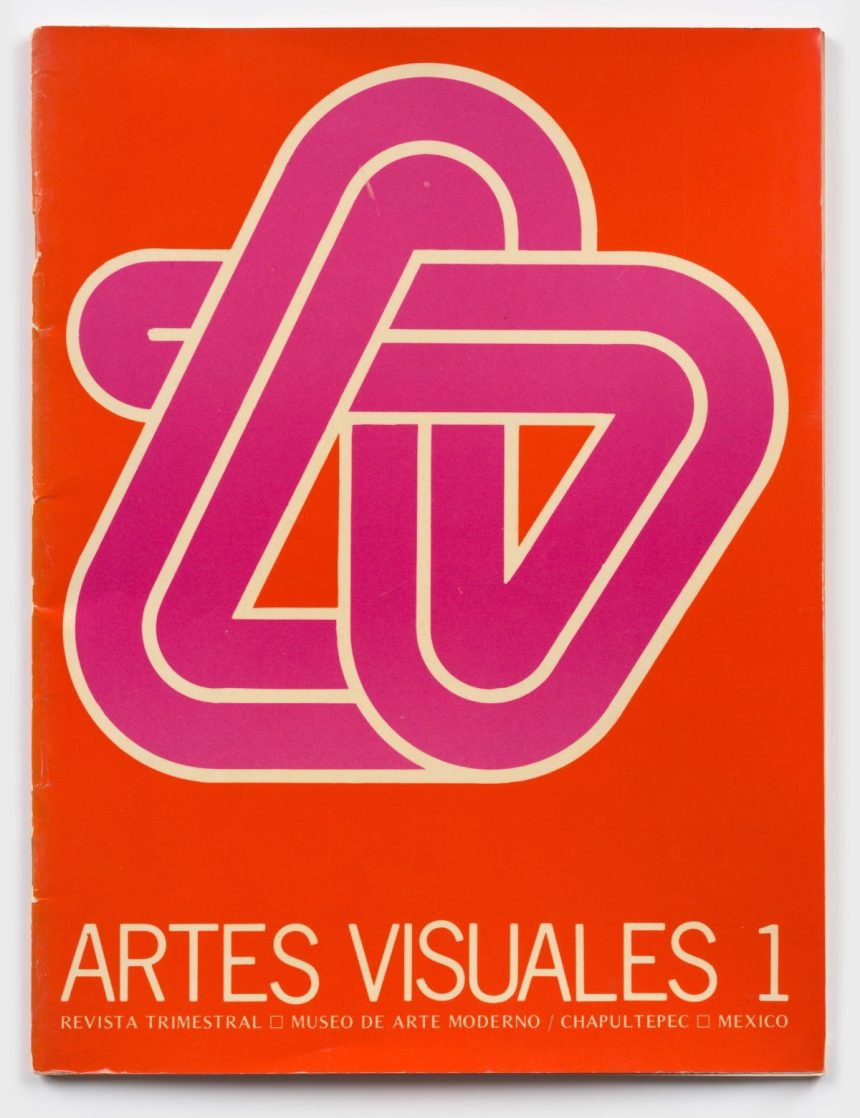

In addition to her influential work in Mexican art scholarship, Stellweg opened doors for Latin American and Caribbean artists on the international art scene, weaving together themes of women’s rights activism, the marginalization of Latine communities in the United States, socioeconomic issues, and institutional critiques into a unified narrative. Among her notable accomplishments is Artes Visuales, a bilingual contemporary arts journal she co-founded and edited at the Museo de Arte Moderno (MAM) in Mexico City from 1973 to 1981. Despite the constraints of a state-funded publication during President Luis Echeverría’s tenure, a time when calls for democratic ideals masked the administration’s role in Mexico’s infamous student killings, Artes Visuales showcased experimental and political art in “subliminal” ways, as Stellweg described in a 2010 essay. Topics ranged from artists’ perspectives on the Panama Canal to discussions on emerging video art, conceptual art, and early accounts of Chicano artists.

“This was in the early 1970s, when few recognized the significance of the Mexican American art scene,” noted Stellweg’s friend, art historian and gallerist Patricia Ruiz-Healy, in an interview with Hyperallergic. “This was the first time in Latin America that serious discussions about the identity of Latin American art were held.”

Taiyana Pimentel, director of the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Monterrey, pointed out that Artes Visuales not only showcased artists but also provided a platform for emerging writers, such as philosopher Manuel de Landa, who published one of his early works in the journal. “It set a standard in Latin American art criticism — an early model that has influenced subsequent publications throughout the region,” she remarked.

Born in 1942 in Bandung, Indonesia — then the Japanese-occupied Dutch East Indies — Stellweg and her family were held in a Japanese detention camp until the end of World War II. She studied in the Netherlands during the 1950s and migrated to Mexico in 1958, immersing herself in the works of José Gorostiza, Alfonso Reyes, and other intellectuals who shaped a vision of Mexican identity that extended beyond post-revolutionary nationalism. Her artistic career began to flourish in the mid-1960s as she worked as an assistant curator to Fernando Gamboa, a prominent museographer and later director of MAM.

Her involvement in international exhibitions such as Montreal’s Expo 67 and the 1968 Venice Biennale placed Stellweg at the center of significant discussions concerning art and modernity. In a 2021 interview, she recounted facing harsh criticism from muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, who opposed the inclusion of works by Rufino Tamayo and artists associated with the Generación de la Ruptura, a movement challenging the dominance of social realism.

Stellweg briefly served as deputy director at the Museo Tamayo in Mexico City in 1979, which featured an exhibition honoring her contributions in 2023. “She belonged to both everywhere and nowhere,” said Andrea Valencia Aranda, co-curator of the exhibition alongside Pablo León de la Barra. “This duality empowered her to engage with artists and movements outside the mainstream.”

After the abrupt closure of Artes Visuales, which she deemed an act of censorship by MAM due to political shifts, Stellweg moved to New York City in 1982. Her Soho apartment became a vibrant center for discourse surrounding Latin American art for many years. Aimé Iglesias Lukin, director and chief curator of Visual Arts at Americas Society, which hosted Stellweg for talks during its 2021 exhibition on Latine artists in New York, shared his memories of Stellweg as a “deeply generous” figure who thrived in sharing her time, space, and ideas with others.

“We were all drawn to her through the art world, but she ultimately taught us about life itself,” Iglesias Lukin recalled, affectionately remembering Stellweg’s warmth and unique sense of humor. “When I went through a painful separation, she told me, ‘Oh, is this your first divorce? Welcome! I’ve had three.’”

Stellweg actively supported U.S.-based artists of Latin heritage, helping them navigate the complexities of their dual existence, and she championed urban and ephemeral art forms, such as graffiti, that challenged conventional expectations. While her tenure at the Museo Tamayo was brief, many of her initiatives during this period left an indelible mark. In 1983, she co-founded the Stellweg-Seguy Gallery, and in 1986, she became chief curator of the Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art, a role she held for three years before establishing her own gallery on Mercer Street. For nearly a decade, she devoted herself to showcasing artists including Ana Mendieta, Liliana Porter, Luis Camnitzer, Hannah Wilke, and Vito Acconci. Porter expressed her admiration, stating, “I was instantly drawn to Carla’s spirit. I had the opportunity to witness her remarkable talent and steadfast dedication to advancing Latin American art, even in less than welcoming environments.”

From 1997 to 2001, Stellweg led the Contemporary at Blue Star, an alternative art center in San Antonio, Texas. She later returned to New York to teach at the School of Visual Arts before eventually returning to Mexico, where she spent her final years.

Stellweg’s willingness to confront political controversies set her apart from many high-profile museum directors. She took part in the Contrabienal, a protest organized in the late 1960s by Latin American artists boycotting the São Paulo Biennial to condemn state repression in Brazil and the widespread terror wrought by military regimes in the region. Stellweg leaves behind a rich collection of writings, now compiled in a volume edited by Edgar Alejandro Hernández, which captures her forthright and insightful commentary on issues ranging from the rise of anti-feminist movements in Mexico to the constraining dynamics of the art market.

“Curatorial projects must feature key ‘protagonists,’ yet wealth-driven moguls often exploit their collections to maximize monetary gains from art investments,” she reflected in a 2015 essay. “Who writes art history these days? Is the entire art narrative solely dictated by private and corporate collectors? Do curator-led initiatives exacerbate this purely financial approach to value? Are distinctions between private and institutional collections still relevant? Are alternatives still viable?”

The impact of Stellweg on the art community and its individuals is vividly represented in an outpouring of tributes and remembrances shared in recent days. Rolando Peña, a Venezuelan-American artist who met Stellweg in New York through progressive artist collectives opposed to the Vietnam War, described their encounter as “like meeting an angel.” Frederik Schampers, Stellweg’s nephew and director at Gladstone gallery in New York, referred to her as a “guiding light… an incredibly powerful woman — highly intelligent, fiercely independent, and deeply dedicated to the artists and ideas she championed.” New York dealer Henrique Faria acknowledged her as a “visionary.”

“Carla was a trailblazer. Her thirst for innovation and her conceptual depth established her as one of the most significant voices of her generation,” commented Patrick Charpenel, director of El Museo del Barrio in East Harlem. “Her passing leaves a void that cannot be filled.”

Stellweg’s archives are preserved at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and Stanford University. An exhibition celebrating the legacy of Artes Visuales, curated by scholar Harper Montgomery in collaboration with the Institute for Studies on Latin American Art, can be viewed at Hunter College’s Bertha and Karl Leubsdorf Gallery in Manhattan until December 13.