In a groundbreaking study, researchers have discovered that symbiotic bacteria living inside insect cells have some of the smallest genomes known for any organism. These bacteria, found in planthoppers, have evolved to live inside specialized cells in the insects’ abdomens, producing essential nutrients that the planthoppers cannot obtain from their plant sap diet alone.

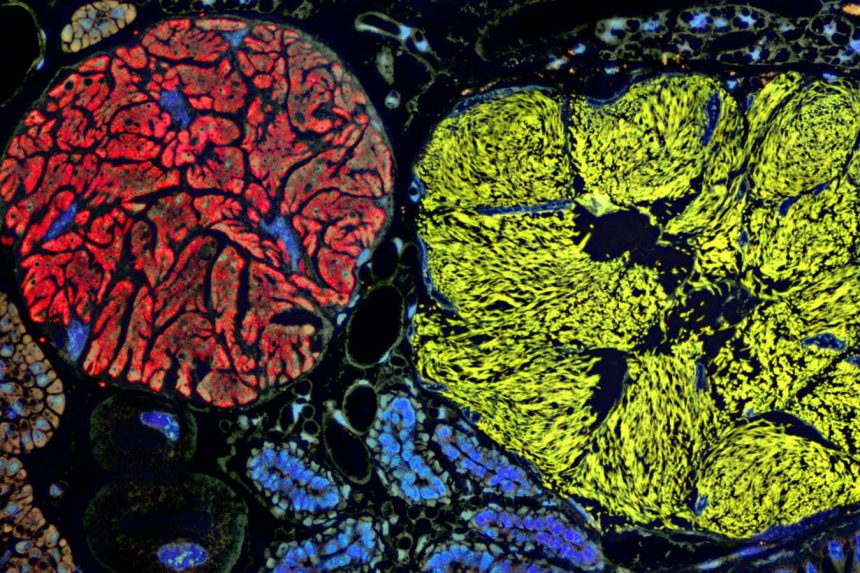

The team of researchers, led by Piotr Łukasik at Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland, examined 149 individual insects across 19 planthopper families to extract and analyze the DNA of the symbiotic bacteria, namely Vidania and Sulcia. What they found was astonishing – the bacterial genomes were incredibly tiny, with some Vidania genomes measuring just 50,000 base pairs in length, making them the smallest genomes known for any life form.

To put this into perspective, the human genome is billions of base pairs long, highlighting just how compact and streamlined these symbiotic bacteria genomes have become over millions of years of co-evolution with their insect hosts. Some Vidania bacteria have only about 60 protein-coding genes, making them comparable in size to viruses, which are not considered to be alive.

The researchers believe that the extreme reduction in gene content in these bacteria may be a result of the insects consuming new foods with nutrients that were once provided by the bacteria, or due to the presence of other microbes that have taken over certain roles. Despite their tiny size, these symbiotic bacteria play a crucial role in producing the amino acid phenylalanine, which is essential for building and strengthening insect exoskeletons.

Interestingly, these highly reduced bacteria bear resemblance to mitochondria and chloroplasts, energy-producing organelles found in animal and plant cells that evolved from ancient bacteria. While mitochondria have even smaller genomes of about 15,000 base pairs, these symbiotic bacteria are unique in that they reside within specialized host cells and are passed down from generation to generation.

Nancy Moran, a researcher at the University of Texas at Austin, notes that while these bacteria share similarities with organelles like mitochondria, there are key differences, such as their location within the host cells and their level of dependence on the host organism.

Overall, this study sheds light on the complex and intricate relationship between insects and their symbiotic bacteria, blurring the lines between what constitutes an organelle and a microbe. The researchers believe that even smaller symbiote genomes may exist, waiting to be discovered and unravel more mysteries of the symbiotic relationships in nature.