Tooth enamel, the hardest substance in the human body, may be at risk of gradual and permanent wear from chewing vegetables.

While plant-based foods are an essential part of a healthy diet, as they provide fiber, vitamins, and minerals, an international team of researchers has found that microscopic plant stones, known as phytoliths, could contribute to dental wear over time, potentially leading to more frequent visits to the dentist.

They designed artificial leaves embedded with these microscopic particles and mounted them on a device that simulates the pressure and sliding motion of chewing against dental enamel samples provided by the local scientists.

According to experimental results published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface, even soft plant tissues caused permanent enamel damage and mineral loss upon interaction with enamel.

It’s quite common for archaeologists to find fossilized remains of teeth as they remain very well-preserved owing to their incredible hardness and durability that can surpass the best of modern engineering materials. The tooth enamel is strong but it’s also brittle, which makes it prone to mechanical degradation due to fractures that happen suddenly when biting forces cause cracks to spread, and wear, which is the slow loss of material over the years.

Scientists have conducted extensive studies on how human tooth enamel breaks and wears down, what causes the damage and how much force it takes to crack. However, an area that is still not fully understood is the effect that tiny particles from outside sources like dust or from the food we eat can have on the enamel.

Phytoliths are microscopic, silica particles that form within the tissues of many plants when the roots take up soluble silica from the soil and the vascular system deposits it in other parts of the body. Previous studies have looked into enamel wear caused by plant phytoliths but the results were often conflicting. Furthermore, these studies failed to realistically simulate how multiple phytoliths, embedded within soft plant matter, interact with tooth enamel during chewing.

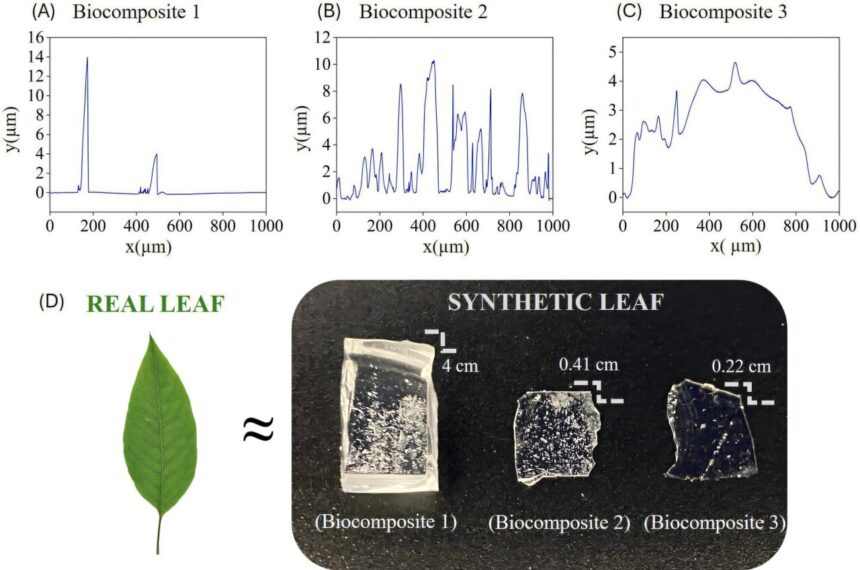

For this study, the scientists designed artificial leaves made from a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)-based matrix with embedded opaline phytoliths obtained from wheat stems and leaves. The resulting leaf, with a thickness and stiffness similar to that of a real leaf, was then fixed to a holder and brought into controlled, repeated contact with healthy human wisdom teeth samples collected from dentists, to simulate the sliding and pressure of chewing.

The physical and chemical changes in the leaf and the dental enamel were analyzed using high-resolution microscopy and spectroscopic techniques. They found that even though the phytoliths themselves break down after repeated contact, they still worsen existing wear on tooth enamel and reduce its mineral content.

A surprising outcome was the main mechanism of wear, which turned out to be a quasi-plastic or permanent deformation arising from weakness in the enamel’s microscopic structure, and not classic brittle fracture. The researchers believe that the new insights into enamel failure can help scientists better understand animal diets, behavior, movement, and environment, by acting as an interdisciplinary interface between the physical and life sciences.

In conclusion, this study sheds light on the potential impact of microscopic plant stones on tooth enamel and highlights the importance of further research in this area to better understand the effects of dietary components on dental health.