Master Criminals and Museum Heists: A Closer Look

Stealing art from a museum is usually a bone-headed thing to do; even the least scrupulous collectors know better than to buy goods that are so recognizably hot. Many museum heists are committed by career criminals who are far better at figuring out how to defeat security systems than they are at planning what they’ll do next. They’re soon caught, whether turned in by an honest dealer or snared in a sting. (For stories of such stings, see Robert K. Wittman’s 2011 memoir about his time with the FBI’s Art Crime Squad.)

Only a few thieves have wrested some value from museum heists, usually by stealing artifacts made from precious metals that can be melted down and disposed of at any shop with a “we buy gold” sign hanging out front. Yogi Berra’s World Series rings disappeared this way. The royal bling recently stolen from the Louvre likely met the same fate.

Museums may have security flaws — the most crucial of which is the unavoidable fact that whoever buys a ticket can get within a few inches of multi-million dollar artifacts — but local authorities are more than eager to make up for these flaws by investigating the hell out of a theft. Thus, unless you can persuade an associate to do the actual breaking in, you likely won’t be free long enough to enjoy your profits, as the rapid arrest of the men who entered the Louvre shows.

Myles Connor is one of the very few people alive to have come out ahead after lifting an artwork from the wall of a museum, as Anthony M. Amore explores in his new book The Rembrandt Heist: The Story of a Criminal Genius, a Stolen Masterpiece, and an Enigmatic Friendship.

Connor grew up in a Boston suburb, making trips to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (MFA Boston) with his grandfather, who passed on a love of Japanese culture. As a teenager in the late 1950s, Connor played rock and roll sets at local clubs, making up for his diminutive stature by riding a Harley Davidson on stage. His charisma was so great that he persuaded one of his fans, the head teller at a bank, to tip him off about when she was expecting an armored car pickup. With the cash all pre-bundled and ready to go, Connor drove off with tens of thousands of dollars.

Through the 1960s, Connor spent his working hours orchestrating bank thefts and importing cocaine and his leisure time collecting art, especially samurai weapons and armor. Many of his acquisitions were legitimate purchases, but he couldn’t resist the odd art theft. Connor, who estimates that he stole from 30 museums and private collections, later told interviewer Ulrich Boser that it felt like being in Aladdin’s cave to have the run of a museum at two in the morning.

Compared to banks, museums were a breeze. It doesn’t appear that Connor won over any curators with his rock and roll gyrations, but he employed his charm in a different manner by introducing himself as an expert in Asian art who wanted to look at artifacts from their storerooms. This was true enough, although he gave an alias. Some curators even left Connor unsupervised to carry out his studies, although he rewarded them for their trust by leaving their collections untouched.

Those who treated the visiting researcher with less consideration soon found their collection diminished. In The Rembrandt Heist, Amore recounts Connor’s memory of his theft from the Boston Children’s Museum, which has a collection of thousands of Japanese artifacts. Shocked that so few of them were ever displayed, Connor picked a dark night to climb up a drainpipe and onto the museum’s roof. He secured a rope around a chimney and rappelled down to the attic, where the collections were stored. Thanks to his research visits, he knew the attic wasn’t alarmed.

Connor emerged with a shoulder bag full of his favorites and climbed back down the way he came. His rationalization for this, as well as his other art thefts, was, as he told Amore, that “any antique that is worth something has been stolen at one point from somebody in its history.”

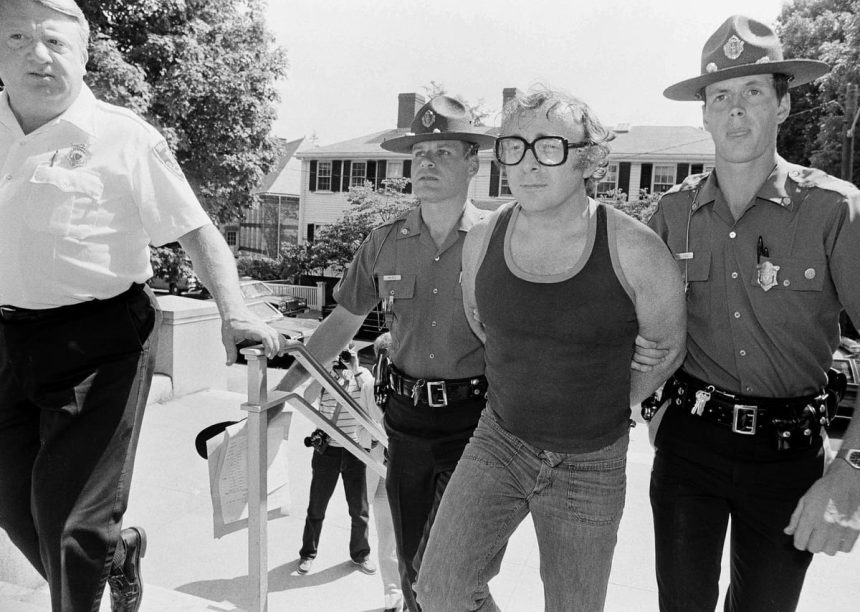

Like Stéphane Breitwieser, another prolific thief who kept a bedroom full of stolen art for his own delectation, Connor avoided getting caught only as long as he relied on his own skill and didn’t sell his prizes. He violated this rule in the early 1970s when he tagged along on a home invasion that was planned, badly, by someone else. Afterward, it didn’t take much for police to track down their suspect. They just waited until Connor finished giving a live interview at a radio station about an upcoming performance.

Connor had already served time, including for wounding a state police officer during a 1967 shootout that ended with him jumping across rooftops in the Back Bay. He didn’t want to go back for the 15 years he was facing for the burglary. Awaiting trial in 1974, Connor floated the idea of surrendering art he had stolen from the Children’s Museum and other institutions in return for a lower sentence, but his lawyer thought the pieces weren’t important enough to tempt the prosecutors. “Nothing short of a Rembrandt could get you out of this,” one advisor told him. Connor took this as a helpful suggestion. Amore explains what happened next in my favorite of his past books, Stealing Rembrandts: The Untold Stories of Notorious Art Heists (2012), written with the arts journalist Tom Mashberg, which served as loose inspiration for the recent movie The Mastermind.

It wouldn’t be the first time that a Boston-area criminal had plotted to use a Rembrandt as a get-out-of-jail-free card. Several years prior, in 1972, the career criminal Florian “Al” Monday hired a couple of burglars to snatch a Rembrandt painting of Saint Bartholomew from the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts, intending to hide it away to use as a bargaining chip if he got caught for some other crime.

Monday’s plan was good. He had scrutinized the guards’ routines and visitor ebbs and flows so thoroughly that the thieves nearly walked out of the museum unnoticed with the painting in a cloth bag. It was only when they crossed the lobby that the guard at the exit yelled out — not because he suspected a theft, but because they were walking on the ancient Roman mosaic installed in the middle of the floor. They used the single bullet Monday had permitted them to load in their gun to shoot the guard before they fled, turning the heist into the first known gunpoint robbery of an American museum. Fortunately, the guard had been giving directions to a visitor who happened to be a nurse and immediately put pressure on his wound, allowing him to make a full recovery.

The thieves ran out of the museum, dropped off the loot with Monday, and went to a bar to celebrate. When a television news report about the heist came on, one of the thieves started bragging about the job. A bar patron who overheard his boasts called the police. Monday had already stashed the Rembrandt in a barn on a pig farm, but it was soon recovered by the FBI.

Connor succeeded where Monday failed by taking a more active role in his heist. His target was a 1632 painting of a young girl in a gold-trimmed cloak, which was on loan to MFA Boston from a private collection. I find the figure uncanny, since Rembrandt appears to have plunked the head of a toddler on the body of a woman, but it was ideal for Connor’s purposes. The painting was less than two square feet and was hanging from a hook, rather than bolted to the wall, just up the stairs from the museum’s less-trafficked back entrance.

Connor knew nighttime security at the MFA Boston was formidable, so he planned for a lunchtime weekday raid, when he knew that visitors were scarce. He brought along a partner to hold a gun while he occupied himself with the painting and donned a blonde wig and sunglasses to cover his distinctive bright red hair and blue eyes.

As is true of many an outing in Boston, most of the planning went into figuring out parking. The back entrance had a circular drive where Connor’s getaway van could wait, along with several other cars driven by accomplices. If the police got on the van’s tail as it wound through the narrow one-way streets surrounding the museum, these cars could stall or crash, blocking off further pursuit. Connor even stationed a female friend in the museum lobby, whose job was to push her baby carriage, complete with a baby doll swaddled in a blanket, into the front doors if an alarm caused the exits to seal.

Connor struck so swiftly that the doll and the crash cars went unneeded. The only difficulty was that he got stuck for a moment in the exit turnstile — they’re difficult to navigate while holding an Old Master. It was long enough for the guard at the exit to grab hold of the art. Connor’s partner had to shake him loose by clubbing him with the butt of his pistol. The guard sprang back up to chase the thieves outside and got his hands on the painting again as it was being chucked into the van. He let go only when he noticed that a machine gun was being pointed at him.

Escaping with the painting was the easy part. Handing it over to the prosecutors without giving them grounds to bust him for the theft was much more difficult, and Amore’s description of these negotiations makes for fascinating reading. Connor received a four-year sentence for his other charges and was never prosecuted for the MFA Boston heist.

It’s hard to know how many others have gotten similar deals, since authorities are understandably reluctant to encourage people with pending charges to target museums. I suspect that Connor’s dedication to doing the job himself is even more rare, since the few publicly known cases of exchanging stolen art for reduced sentences have involved someone who only later acquired the pieces, after the original theft.

I can see why Amore calls Connor “one of history’s great criminal geniuses,” given that he got away with the MFA Boston heist. But this title seems an exaggeration, considering that Connor was caught so many other times and served decades in prison. Even his triumph over the Rembrandt return was short-lived. Shortly after he completed that sentence, he sold a few of his stock of stolen paintings along with a kilo of cocaine to a shady New York art fence, who was actually an undercover FBI agent.

Connor was sentenced to 20 years for that endeavor. While he was behind bars, the man to whom he had entrusted his art collection, worth an estimated $5 million, sold it to feed a heroin addiction. Everything valuable has already been stolen, indeed.

The Rembrandt Heist: The Story of a Criminal Genius, a Stolen Masterpiece, and an Enigmatic Friendship (2025) by Anthony M. Amore is published by Pegasus Crime and is available online and through independent booksellers.