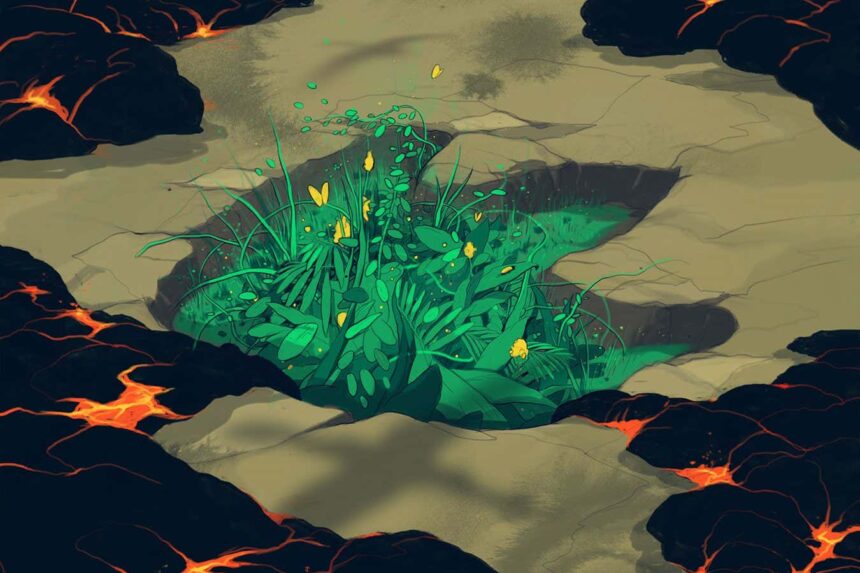

The end-Permian mass extinction, also known as the Great Dying, is considered the deadliest event in Earth’s history, nearly wiping out all life on the planet 252 million years ago. However, recent discoveries at South Taodonggou in China have revealed an ancient ecosystem where plants and animals were thriving just 75,000 years after this catastrophic event. This revelation has led to a reevaluation of the impact of the end-Permian extinction.

Palaeontologist Hendrik Nowak from the University of Nottingham challenges the traditional view of the end-Permian event, pointing to fossil pollen from other sites that suggest minimal disruption. He argues that there may not have been a mass extinction for plants during this period. This perspective is supported by studies on insects and four-limbed land animals, which also indicate limited impact from the extinction event.

These findings have sparked controversy in the scientific community, with some experts questioning the extent of the end-Permian mass extinction. Spencer Lucas from the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science even suggests that land-dwelling organisms may have never experienced a mass extinction event. This radical rethink could rewrite the history of life on Earth, challenging the notion of five mass extinctions on land and reshaping our understanding of evolutionary patterns.

Overall, the new insights into the end-Permian mass extinction present a paradigm shift in our understanding of Earth’s history and the resilience of life in the face of catastrophic events. This ongoing research opens up new avenues for exploration and could lead to significant revisions in our understanding of the evolutionary processes that have shaped the world we live in today.