New Discoveries Illuminate Ancient Nomadic Cultures in Saudi Arabia

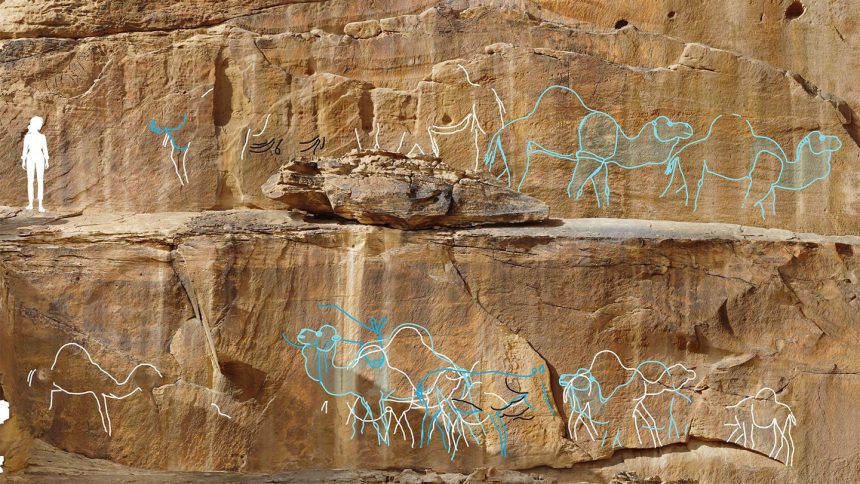

The camels etched into the rocks of Jebel Misma stand as a breathtaking testament to our past, frozen in time for 12,000 years. “They are really spectacular,” exclaimed paleoanthropologist Michael Petraglia. “They’re beautiful, monumental.” These extraordinary engravings represent a herd of camels skillfully carved into a towering cliff that dominates the otherwise flat landscape of Saudi Arabia’s Nefud desert.

The life-sized engravings, alongside approximately 150 newly documented petroglyphs, date back to a period between 12,800 and 11,400 years ago, as reported by Petraglia and his team in a recent study published on September 30 in Nature Communications.

While rock art has previously been found in Saudi Arabia, these newly discovered petroglyphs are much older than those from the Neolithic period, which dates back only about 8,000 years. The engravings at Jebel Misma, Jebel Arnaan, and Jebel Mleiha—rock outcrops in a remote region of the Nefud near its southern edge—are not only older but considerably more significant. Petraglia, who is the director of the Australian Research Center for Human Evolution at Griffith University in Brisbane, suggests that these engravings were likely intended to mark territory or indicate nearby water sources due to their visibility from great distances.

Dark History Revealed Through Art

The fresh discoveries emerged from a project led by Petraglia known as Green Arabia, aimed at understanding the prehistoric environment of the Arabian Peninsula. Recent findings indicate that the region has experienced lush and verdant periods over the past 8 million years, suggesting that the Sahara and eastern desert areas were once considerably wetter.

Petraglia and his colleagues believe that the initial rock engravings at Jebel Misma and its surrounding areas were likely created by the first nomadic peoples to migrate to this region following the Last Glacial Maximum, which concluded around 19,000 years ago. As rainfall revived the landscape, temporary desert lakes—called “playas”—formed, inviting diverse fauna such as camels, gazelles, aurochs, and ibex. These animals, in turn, attracted nomadic human hunters who relied on them for sustenance.

The engravings made by these hunters were incised into the natural dark “varnish” that develops on desert rocks, revealing the lighter sandstone beneath. An analysis of these engravings indicates that they were created over four distinct phases. The oldest, dating back more than 12,000 years, depicted small, stylized female figures, often with exaggerated features. Following this, a second phase involved larger stylized human figures.

The third and most impressive phase, which lasted until about 11,000 years ago, features remarkable animal engravings, some measuring up to 3 meters in length, characterized by distinct individual traits. The final phase presents a more stylized and cartoonish representation of animals, highlighting the evolution of artistic traditions over time. The last verdant era in Arabia came to a close approximately 6,000 years ago, ushering the Nefud back into arid conditions.

Connecting with Our Past

Excavations conducted near the petroglyphs uncovered stone tools and other artifacts, suggesting that the artists had connections with other prehistoric groups in the Eastern Mediterranean. However, the distinctive size and artistic style of these engravings illustrate the emergence of a new tradition among these nomadic peoples. “This is a brand new phenomenon,” says Petraglia, emphasizing the monumental nature of the rock art.

Paleoclimatologist Paul Wilson from the University of Southampton described the research as a significant contribution to understanding how prehistoric humans adapted to climatic changes. “Just like its African counterpart [the Sahara], the Arabian desert is rich with prehistoric engravings and paintings, providing tangible evidence of human occupation,” he notes.

Archaeologist Anna Belfer-Cohen, a professor emerita at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, highlights the importance of these findings, suggesting that the evidence supports the notion of evolving lifestyles among prehistoric peoples in Arabia. Petraglia and his team’s work sheds light on a previously unexplored region and its rich prehistoric narrative. “This tells the story of a region that was for years terra incognita, so much so that people did not even consider exploring it,” Belfer-Cohen asserts. “These findings are eye-openers.”

This unique article, designed for integration into WordPress, retains key points and HTML structure while conveying the significance and context of the new archaeological discoveries in Saudi Arabia.