Nestled in a distinguished yet approachable former carriage house on the Upper East Side, the Society of Illustrators presents a delightful venue for art enthusiasts. Its eclectic collection of artworks is displayed salon-style, complementing the charm of a 19th-century staircase, fostering an intimate atmosphere where visitors can explore captivating illustrations.

Something Else Entirely: The Illustration Art of Edward Gorey offers a particularly welcoming experience. Upon entering the third floor, visitors encounter a polished wood bar on one side, with patio doors opening to a sunny balcony adorned with cafe tables on the other. With jazz setting the mood, I ordered a latte and admired 80 original Gorey drawings spanning from 1950 to 2000. It’s hard to envision a more perfect afternoon in the city. Yet, I walked away wishing the exhibition could have made a stronger case for the profound impact and lasting significance of Gorey’s unique perspective.

“I’ve been killing children in my books for years,” Gorey amusingly remarked in a 1977 interview. This enigmatic New York artist—part proto-Goth, ballet aficionado, and fur-fashion luminary who never fathered children—has conjured unforgettable imagery, such as small legs peeking from beneath a sprawling rug in a somber Edwardian setting. “G is for George smothered under a rug,” we read, evoking a flood of fears that haunt us all.

What fascinates me about Gorey is his expertly calibrated aesthetic, navigating the fine line of depicting death while simultaneously allowing his whimsical characters to flourish. He masterfully detaches the morbid circumstances he illustrates, rendering them both dryly humorous and absurdly whimsical. Yet, as I delved deeper into his expansive body of work—including Dada-inspired murder mysteries, fantastical creatures, and even provocative adult narratives (despite his claims of being largely asexual)—I was eager for a richer exploration.

This exhibition’s challenge lies in its focus on his role as a familiar illustrator, limiting its selection to his day work rather than diving into the full breadth of his 116 books, which represent his nighttime musings. While it rightly aligns with the mission of the Society of Illustrators and captivates industry interests, it narrows the lens through which to understand his art.

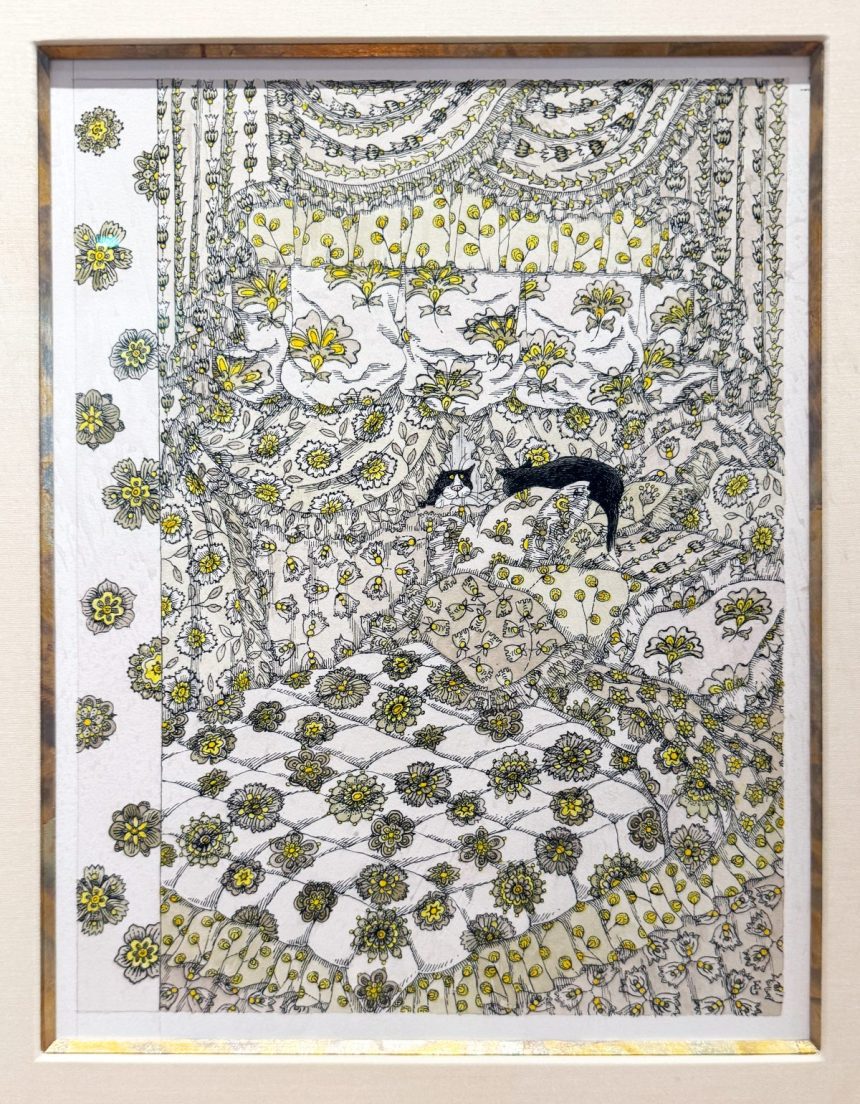

Nonetheless, glimpses of Gorey’s unique visions still appear even in these commercial endeavors. His illustrations for Hilaire Belloc’s Cautionary Tales for Children (1907)—his predecessor and clear influence—intertwine seamlessly with his eccentric fascinations. Other artworks from A Clutch of Vampires (Raymond T. McNally, 1974) exude his signature macabre charm. With a Tony Award to his name for designing the stage for the 1977 Broadway rendition of Dracula, his New Yorker cover featuring two cats comfortably lounging on a botanically elaborate bed, originally submitted in 1992 and published posthumously in 2018, highlights his love for felines and intricate pen-and-ink detail. However, the exhibit seems to shy away from the deeply unsettling narratives like that of the ill-fated boy crawling into darkness. While there’s an intriguing variety displayed, it feels like Gorey’s more eccentric spirit isn’t wholly unleashed.

Experiencing his work up close is rewarding in its own right. The lustrous black ink, the intricacies of cut-and-paste, and the hand-drawn printer’s crop marks—these details transport us back to the pre-computer era of midcentury publishing, when Gorey reigned as an illustrative icon, draped in his luxurious double-breasted coyote and seal-fur coats. We also observe the evolution of his style: the early peculiar oblong heads and elongated feet gradually transition to the deadpan figures that became his trademark by 1959’s Monkey’s Paw. It’s no wonder authors rejoiced upon learning that Gorey would illustrate their stories.

Many of these works are displayed publicly for the first time, and that’s praiseworthy—as is depicting Gorey as a resourceful illustrator thriving in a competitive market, rather than simply a mythic figure supported by wealthy benefactors. I am cautious of shows that merely replicate an artist’s myth rather than delve into complexities, and this exhibition indeed adds layers to Gorey’s persona. Nevertheless, what is conspicuously absent are the unforgettable pieces that linger in memory—the haunting image of little George from 1963’s The Gashlycrumb Tinies (his most beloved book), or the grotesque yet fascinating illustrations found in Beastly Baby, self-published in 1962, which portrays a parent’s repulsion towards their offspring in a harrowing manner. This absence underscores the very essence of free artistic expression that his commissioned work was meant to elevate. Perhaps this exhibition inadvertently reveals the necessity for an artist to embrace the freedom of personal exploration amid commercial assignments.

A friend of Gorey’s once remarked that he “journeyed vastly between his ears.” It’s this enigmatic depth that continues to captivate generations of goths, steampunks, and creatives like Tim Burton. More crucially, in an era where each day unfolds against a backdrop of genuine horror and surreal absurdities, Gorey’s artwork offers the strangest yet most comforting escapism.

Something Else Entirely: The Illustration Art of Edward Gorey is on display at the Society of Illustrators (128 East 63rd Street, Upper East Side, Manhattan) until January 3, 2026. The exhibition has been organized by the institution.