The recent ousting of Nicolás Maduro from the presidency in Venezuela marks a pivotal moment following over two decades of socialist governance under Hugo Chávez and Maduro, a period riddled with expropriation, economic mismanagement, and political oppression.

As uncertainty looms over Venezuela’s economic and political landscape, economic theory can provide crucial insights—and a few stern warnings. One key lesson emphasizes the perilous allure of relying exclusively on the oil sector for economic recovery. The future of Venezuela hinges on the quality of its institutional and policy decisions going forward.

Currently, the judiciary, electoral authorities, public prosecutors, and police in Venezuela lack independence. Therefore, the foremost priority must be the restoration of individual and political rights through the reform of these critical institutions. This will enable the Venezuelan populace to hold their political leaders and government officials accountable once again.

Next, it is essential to re-establish private property rights and cultivate a free enterprise environment that can unlock the innovative potential of the Venezuelan people.

Moreover, leadership must focus on crafting effective foreign-exchange policies and managing oil revenues. These are vital to avoid a resurgence of dependency, rent-seeking behavior, and economic stagnation.

A political transition that incorporates substantial electoral reforms and offers credible guarantees for fair competition could pave the way for a gradual normalization of relations with the United States. This thawing of relations might facilitate the lifting of some sanctions and encourage the re-entry of private—particularly foreign—oil companies into Venezuela’s energy sector. Given the nation’s vast proven reserves and its deteriorated yet recoverable infrastructure, even minor enhancements in institutional quality could lead to significant increases in oil production and export revenues. Such revenues would provide a rare chance to stabilize public finances, begin repaying defaulted foreign debts, and restore Venezuela’s credibility in global capital markets.

However, this opportunity is fraught with well-documented risks. The foremost concern is the threat of Dutch disease—the phenomenon where resource booms lead to currency appreciation, undermine non-resource tradable sectors, and reinforce a non-diversified economic structure. Venezuela’s historical experience serves as a cautionary tale. Past oil booms have seen exchange-rate appreciation and fiscal irresponsibility devastate agriculture and manufacturing, heighten import dependence, and solidify the power of rent-seeking coalitions. Thus, any serious reconstruction strategy must treat exchange-rate policy as a cornerstone of economic reform, not a technical afterthought.

To avert Dutch disease, it is crucial to resist sustained appreciation of the local currency, even in the face of rising export revenues, as previously argued here. An appreciating currency would render non-oil exports uncompetitive and stifle the revival of key sectors essential for long-term growth and employment. While this does not necessarily suggest a return to rigid exchange controls—with their disastrous consequences well-documented in Venezuela—it does indicate the necessity for a meticulously designed regime. Strategies such as sterilizing foreign-exchange inflows, accumulating external assets, and institutional mechanisms to curb excessive domestic spending of oil revenues must all play a role in maintaining a competitive real exchange rate.

Closely linked to a successful foreign-exchange policy is the management of oil rents. The primary political economy challenge for a post-socialist Venezuela will be ensuring that these rents do not fall prey to entrenched interests, whether public or private. Without credible constraints, oil revenues can fuel corruption, clientelism, and fiscal irresponsibility, eroding both democracy and economic freedom. Therefore, establishing a dedicated “sink fund” warrants serious consideration. Unlike a traditional sovereign wealth fund aimed at maximizing returns or smoothing consumption, a sink fund would have a clear and transparent mission: systematically repaying Venezuela’s foreign debts over a specified timeline.

Diverting a significant portion of oil revenues into such a fund could yield multiple advantages. Firstly, it would alleviate the immediate pressure to spend domestically, thus supporting exchange-rate stability and mitigating Dutch disease. Secondly, it would aid in rebuilding Venezuela’s reputation as a responsible borrower, thereby lowering future borrowing costs and expanding access to international finance. Lastly, by placing oil revenues beyond the discretionary control of daily politics, a sink fund would curtail opportunities for rent-seeking and demonstrate a genuine commitment to fiscal discipline.

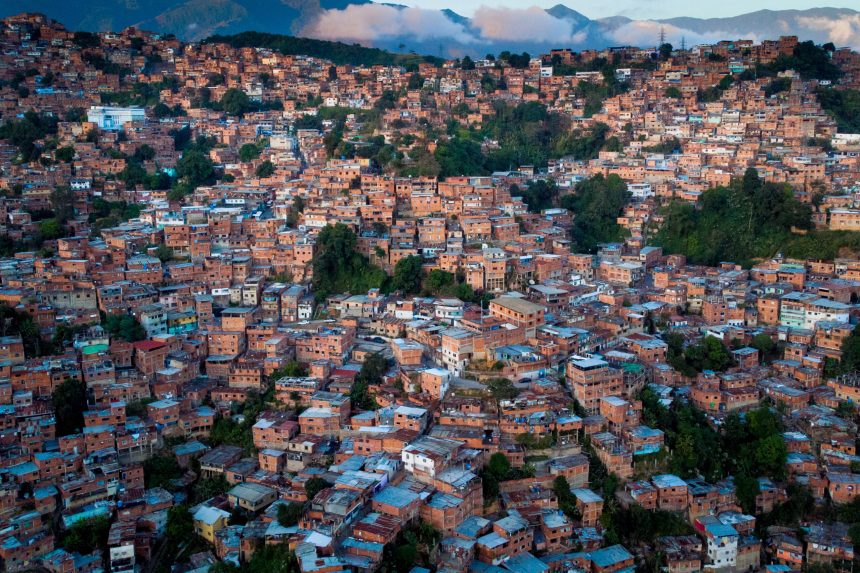

Over time, reinstating essential protections for private property and free enterprise would allow economic activity outside the oil sector to recover. Historically, Venezuela had a relatively diversified economy compared to regional standards, with notable strengths in agriculture, manufacturing, services, and human capital-intensive industries. While much of this capacity has been damaged or pushed into the informal sector, it has not entirely disappeared. The Venezuelan diaspora—now numbering in the millions—represents a crucial reservoir of skills, entrepreneurial experience, and international connections. If institutional reforms are credible and sustainable, many expatriates may choose to return or invest from abroad, thereby accelerating reconstruction and diversification.

Perhaps, the political demands of a struggling populace for public aid could be redirected by fostering profit-making and income generation through the private sector. Without this understanding and implementation, the allure of rent-seeking will be irresistible, leading to the dissipation of oil rents and the corruption of political representation, as government revenues become detached from the broader welfare of Venezuelans and their economy.

In this larger context, exchange-rate policy and oil-rent management should be viewed as foundational elements for a deeper transformation. The aim is not solely macroeconomic stabilization but the reconstitution of a society where economic opportunities are decoupled from political privilege. By avoiding currency overvaluation, protecting oil revenues from exploitation, and prioritizing debt repayment over short-term consumption, a post-Maduro Venezuela could establish the groundwork for sustainable growth and genuine reintegration into the global economy.

Achieving this vision will not be easy, and success hinges on a combination of luck and political will, as well as technical design. However, if conditions for political normalization, institutional reform, and renewed oil production hold true, the prudent management of exchange rates and rents could ensure that Venezuela’s next encounter with resource abundance becomes a source of recovery rather than just another missed opportunity.

Leonidas Zelmanovitz is a Senior Fellow at the Liberty Fund and a part-time instructor at Hillsdale College.