While some critics argue that Christopher Columbus’s voyage was a mere footnote in history—claiming he did not truly “discover” the New World since Indigenous peoples already called it home—this perspective overlooks a pivotal point: Columbus’s expedition integrated isolated continents into a broader narrative of global connectivity. Before Columbus, while Indigenous peoples thrived in their respective regions, they were unaware of a world teeming with cultural diversity beyond their borders. His journey initiated a radical transformation that intertwined continents and civilizations, forever altering the fabric of history.

In contrast to Vasco da Gama, whose navigation merely charted a route to well-known lands, Columbus expanded the geographical understanding of his era. His expeditions laid the groundwork for the intricate tapestry of global civilization we now experience. Columbus has often been upheld as a figure emblematic of Western civilization and Christianity, credited with ushering in numerous advancements that followed in the wake of his journey.

Historically, the claims of other groups, notably the Vikings and the Chinese, seeking to assert earlier discoveries of America, merit examination. The Vikings established fleeting settlements in North America around 1000 CE, yet their engagements lacked ambitions for colonization. Their Greenland colony remained in a nascent state, confronting challenges from indigenous populations and environmental shifts culminating in abandonment by the 14th or 15th century amidst the onset of the Little Ice Age. Critically, the Norse voyages resulted in no significant, lasting impact—no established maps, no trade routes, and no sustained exchanges that would reshape the Americas.

The theory positing that Admiral Zheng He of China reached America in 1421 has largely been dismissed by historians as lacking substance. Scholars have critiqued Gavin Menzies’s book upholding this claim as “spurious,” citing its reliance on circular reasoning and the absence of verifiable evidence. Established records confirm that Zheng He’s expeditions traversed the East African coasts and the Indian Ocean but fell short of crossing the Pacific.

Even hypothesizing a Chinese “discovery” of America fails the impact assessment, akin to the Viking saga. There’s a notable lack of records indicating that such an event influenced historical trajectories meaningfully. No mapping, no settlements, and no voyages back to China materialized to engage with the Americas or transform global civilization.

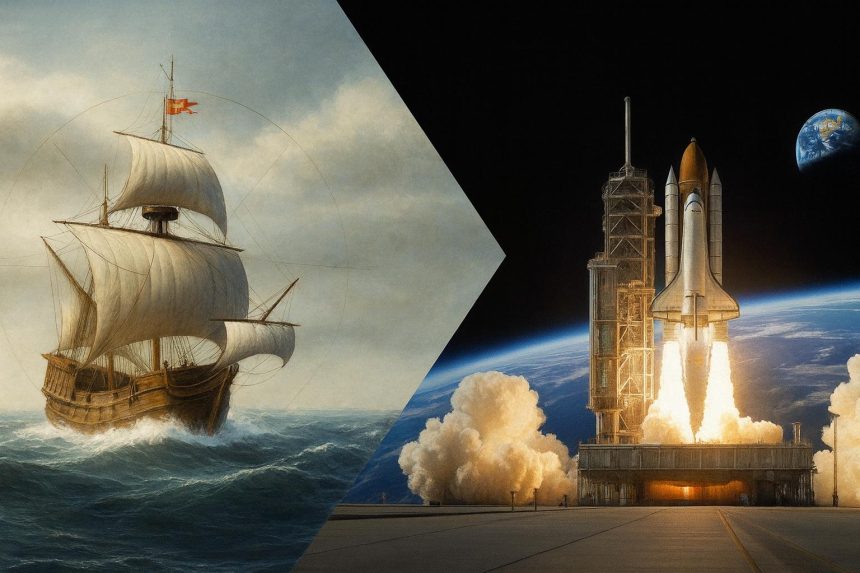

In stark relief to these earlier claims, esteemed astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson has posited Columbus’s landing as “the most significant event in human history.” Tyson articulates that it effectively reunited branches of humanity that had been sequestered from one another for approximately 10,000 years following the watery demise of the Bering land bridge. This renaissance of connection forestalled human speciation and forged a singular, interconnected global populace.

Columbus’s voyage set in motion what historians famously term the Columbian Exchange, a monumental interchange of flora, fauna, people, diseases, and culture between the Old and New Worlds. This exchange irrevocably catalyzed historical evolution.

American staples like corn, potatoes, and cassava engendered agricultural revolutions across Europe, Asia, and Africa, staving off famine and stimulating population booms, especially post-1700. By reconnecting distinct ecosystems that had independently evolved since the Ice Age, the Columbian Exchange indelibly modified ecosystems and societies worldwide.

The subsequent European colonization manifested in settlements such as Jamestown (1607) and Plymouth (1620), which became the early roots of what is now the United States. Innovative governance structures, from the Mayflower Compact to the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1619, laid the groundwork for democratic principles and civic engagement that would shape the nation’s political evolution. This trajectory culminated in George Washington being inaugurated as the first president of the United States on April 30, 1789, in New York City, at the time the nation’s capital. Washington symbolized not only America’s inaugural president but also the first democratically elected leader in modern history—an event that significantly facilitated the dismantling of feudal systems across multiple continents, which had perpetrated widespread poverty and ignorance.

The interplay of American capitalism, property rights, and the Industrial Revolution collectively fostered the emergence of a middle class, enhancing living standards globally, with Columbus serving as the initial catalyst of this transformation.

Dispelling prevalent myths aims to undermine Columbus’s achievements, such as the erroneous claim that he proved the Earth was round. This notion is easily countered—educated individuals had possessed this understanding for centuries. Historian Jeffrey Burton Russell asserts, “no educated person in Western civilization from the third century B.C. onward believed the Earth was flat.” Renowned Greek scholars like Pythagoras and Aristotle had already demonstrated the sphericity of our planet as early as 600 B.C. using astronomical observations.

Stephen Jay Gould has aptly noted that “there never was a period of ‘flat Earth darkness’ among scholars,” as the medieval intellectuals universally accepted Earth’s spherical nature. The enduring myth that Columbus confronted a flat Earth was forged in 1828 by Washington Irving in his literary work, The Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, marred with dramatic embellishments.

Columbus’s objective was decidedly pragmatic; he sought a westward maritime route from Spain to Asia’s lucrative trade centers. While scholars recognized Earth’s configuration and acknowledged the potential of reaching Asia by sailing west, none had undertaken this journey. Columbus’s enterprise transformed the theoretical into reality. Although he miscalculated Earth’s circumferences and underestimated Asia’s expanse, supposing Japan was merely 8,000 miles from Spain, his misjudgment inadvertently led to one of history’s monumental revelations: the existence of the Americas, stunningly oblivious to Europe at the time. Had the Americas not existed, Columbus might have reached Asia eventually in some improbable way.

Ultimately, despite his persistent assertion of having found a path to Asia, Columbus’s voyages opened a floodgate of exploration possibilities. His daring and vision laid the framework for Atlantic crossings, culminating in 1521 with Magellan’s expedition, which successfully navigated the Pacific and completed the first circumnavigation of our planet. Columbus’s pivotal journey catalyzed subsequent events, fundamentally reshaping the trajectory of human history.