Intro. [Recording date: June 17, 2025.]

Russ Roberts: Today is June 17th, 2025, and joining me is economist, author, and podcaster Mike Munger from Duke University. He is the host of the podcast The Answer Is Transaction Costs. This marks Mike’s 50th appearance on EconTalk, earning him the title of the Babe Ruth or Henry Aaron of our guest lineup—or perhaps Barry Bonds, although I’m skeptical of any performance-enhancing substances in his background. Last time he was here, in January 2025, we discussed the impact of DOGE and Elon Musk. It appears he was spot on with that prediction. Welcome back to EconTalk, Mike.

Michael Munger: Thanks, Russ. It’s quite a milestone, and hard to believe it’s been 50 times. I guess that means you’re getting on in years.

Russ Roberts: Indeed. Well, EconTalk is aging gracefully.

Michael Munger: You, on the other hand, seem to have found the Fountain of Youth.

Russ Roberts: Absolutely! Now, just a quick note for our listeners: we’re recording during the ongoing Iran-Israel conflict that began recently—its timeline is debated, with some claiming it started days ago and others saying it’s been brewing for over a year. I’m recording from home as I need to be near a bomb shelter, so if there’s any unexpected noise, bear with me.

But I mention this only to explain any potential distractions in the audio or video quality.

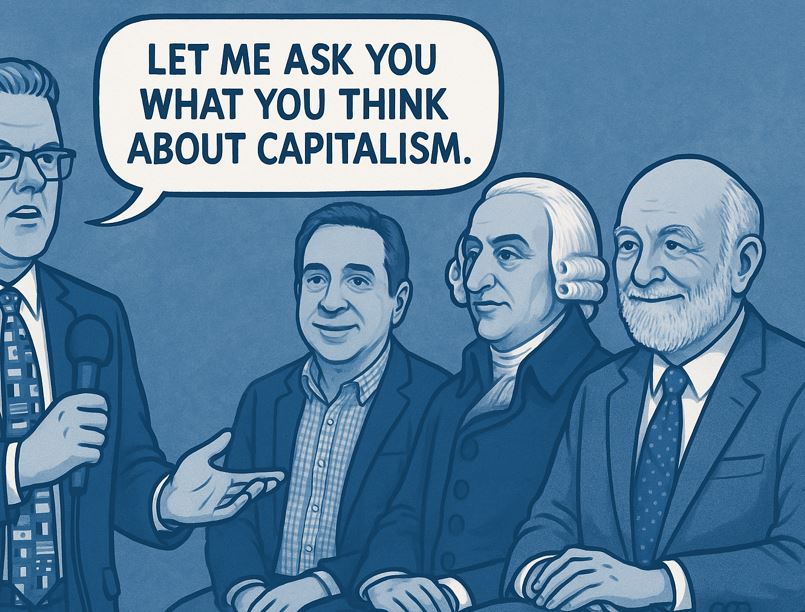

Russ Roberts: Today, we’ll explore the essence of capitalism—a broad enough topic to encompass almost any discussion we have. Mike, you have a unique perspective on various facets of economic activity, viewing capitalism as just one of three key components. Let’s break those down, starting with your overarching framework.

Michael Munger: I developed this framework after noticing that my students at Duke, even those who claim to support capitalism, often lack a clear understanding of what it is. They struggle to define it accurately. It dawned on me that I, too, was a bit unclear. So, I devised a way to explain it.

Russ Roberts: Fascinating.

Michael Munger: I conceptualize it similarly to the stadial theory from the Scottish Enlightenment, which posits that societies progress through stages: starting from hunting and gathering, moving to domestication of animals, then to agriculture, and finally reaching a commercial society.

In my view, the largest circle in this conceptual Venn diagram represents voluntary exchange, which all human societies engage in. A subset of these societies evolve into markets, and the smallest circle encompasses those that develop capitalism. Understanding these stages is crucial because engaging in voluntary exchange fosters notions of property rights and a sense of propriety—essential for developing markets.

Market institutions must be well-established for a society to fully embrace capitalism.

To visualize this, think of three concentric circles: the largest represents voluntary exchange, the next represents markets, and the smallest represents capitalism. All capitalist societies engage in voluntary exchange and have markets.

Russ Roberts: Just to clarify: all capitalist economies encompass markets and voluntary exchange.

Michael Munger: Correct. They also require the institutions that have organically developed throughout these stages. A sense of propriety in exchange, a currency, and institutions that reduce transaction costs are all vital. Thus, capitalism builds upon the foundations of voluntary exchange and markets.

Russ Roberts: We’ll delve deeper into that.

Russ Roberts: Let’s start with the most fundamental concept: voluntary exchange, often referred to as mutually beneficial exchange. What does this entail, and why is it significant?

Michael Munger: In a voluntary exchange, both parties emerge better off. I’ve conducted extensive research on what constitutes a truly voluntary exchange, or “euvoluntary” exchange, which I can share in the show notes for those interested.

Russ Roberts: We’ve also covered this in a previous episode, so for those who prefer listening over reading, there’s that option.

Michael Munger: For the connoisseurs of our past discussions, yes.

Russ Roberts: That’s what I meant.

Michael Munger: It’s easy to overlook the cumulative power of numerous small improvements. Economists often focus on marginal changes, but the aggregate effect of many small enhancements can be more significant than any singular major improvement.

When we engage in an exchange, both parties experience a form of consumer surplus, which economists measure to assess how much better off someone is post-exchange. For example, if I value an item at $10 but purchase it for $4, my consumer surplus is $6.

Even in a barter system, both parties can achieve consumer surplus. If I have an apple and you have a banana, and we prefer what each other possesses, the exchange makes us both better off. Although the total quantity of goods remains unchanged, the distribution improves, enhancing overall satisfaction. This illustrates the importance of voluntary exchange.

Russ Roberts: A quick note: In reality, exchanges come with uncertainties. A refined definition would state that we engage in exchanges with the expectation of benefiting, but sometimes we might be disappointed—like when I find I dislike bananas after all.

Michael Munger: Exactly. Our expectations play a crucial role. People might misjudge and believe they will benefit from a trade, only to find they do not like the item they received. This speaks to the nature of exchange and barter.

Michael Munger: Adam Smith’s second-favorite quote comes to mind: people have an innate “propensity to truck, barter, and exchange.” It’s akin to fundamental human needs like hunger or thirst; there’s a natural human drive to engage in trade.

However, while exchange redistributes existing goods, it doesn’t necessarily increase their total quantity. This is a vital point.

Russ Roberts: I want to dig deeper into that idea. In our pre-recording discussion, I realized I hadn’t fully grasped the implications of Smith’s thoughts on this, which encompass not just the propensity to trade itself but also the desire to improve our circumstances through exchange. Would you agree?

Michael Munger: Absolutely. This desire extends to improving not just ourselves, but also those with whom we exchange. The fairness of an exchange matters; we want both parties to benefit.

In most voluntary exchanges, particularly local ones, we see a shared commitment to fairness. People generally aim to engage in exchanges that benefit both sides, which cultivates a culture of propriety and trust.

Russ Roberts: You’re referring to Smith’s earlier work, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, where he articulates, “Man naturally desires not only to be loved but to be lovely.” This captures the essence of wanting respect and esteem through honorable conduct. The intersection of self-interest and moral consideration is crucial here, isn’t it?

Michael Munger: Certainly. Smith’s notion of propriety ties back to how we evaluate one another’s actions. It involves an “impartial spectator” perspective—imagining how others would judge our exchanges.

So, while initially our exchanges are driven by self-interest, they evolve into a commitment to fairness and mutual improvement, fostering a deeper ethical consideration in trade.

Russ Roberts: The empathetic aspect you mentioned is essential. It aligns with the idea that understanding others’ needs enhances our effectiveness in trade. By fostering this reciprocal relationship, we improve not only our own lot but also contribute positively to our trading partners.

Michael Munger: Exactly! The separation of self-interest and ethical considerations that modern economists often make would baffle Smith. He saw them as intertwined—improving oneself and one’s character go hand in hand.

Russ Roberts: To summarize our discussion on voluntary exchange: when we engage in it, both parties expect to be better off. This rearrangement of goods leads to enhanced satisfaction and relies on the foundation of trust built through repeated interactions, which in turn helps mitigate opportunistic behavior. In a close-knit society, unethical traders risk social ostracism. While exchange is beneficial, it only scratches the surface of the potential for commercial interactions to elevate our material well-being. Let’s move on.

Michael Munger: Before transitioning, I want to emphasize that while voluntary exchange appears localized and limited, it remains the bedrock of all advanced societies. The true brilliance of Smith’s insights lies in recognizing that scale is essential for achieving widespread prosperity—opulence requires a society capable of producing more, not just redistributing existing goods.

The key transition involves moving from personal commitment to mutual benefit to a societal commitment to justice, defined by not infringing on others’ rights or breaking promises. This commitment to justice allows societies to develop markets, which serve as institutions that reduce transaction costs associated with impersonal exchanges.

These institutional frameworks are crucial for enabling one-off transactions where trust is paramount, even among strangers—fostering a culture of justice and reliability in economic interactions.

Russ Roberts: I’d like to discuss the division of labor and its significant implications. I previously dedicated an episode to connecting Smith’s ideas with Ricardo’s insights on trade.

Let’s explore how the division of labor functions. For example, if I have a fertile land suited for bananas and you for apples, we can each specialize, enhancing our productivity through trade rather than trying to do everything ourselves.

Michael Munger: Many jump straight to comparative advantage when discussing division of labor, but Smith also recognized that specialization enhances productivity, even among identical individuals. The more we focus on a specific task, the better we become at it, leading to an accumulation of knowledge and skills.

To illustrate, consider a scenario with four individuals each attempting to produce clothing, shoes, fish, and vegetables independently. Initially, we struggle and remain impoverished. But as we identify each person’s strengths, we begin to specialize: one person becomes a dedicated shoemaker, another a fisherman, and so forth. This specialization allows us to produce more efficiently.

Russ Roberts: This concept of specialization acts as a catalyst for prosperity. However, it’s crucial to note that an uncoordinated effort by everyone to produce all goods yields only marginal gains compared to the exponential benefits of specialization.

Michael Munger: Correct. As we specialize, we become more adept, and even if we started as equals, our productivity diverges significantly over time. This is the underlying principle of artisanal specialization, where individuals refine their skills and create a surplus of goods.

As specialization deepens, we not only improve our dexterity but also begin to innovate—developing new tools and techniques that further enhance productivity.

Russ Roberts: I want to reiterate the transition we’ve been discussing. Initially, we possess a fixed quantity of goods, but specialization allows us to enhance overall production. The total output increases due to specialization, dexterity, and technological advancements.

This exponential increase highlights a critical point: as we expand our production capabilities, we also unlock new opportunities for trade and exchange.

Michael Munger: Absolutely. The transition from simple trade to a more complex division of labor fundamentally alters the economic landscape. When we specialize, we unleash a significant increase in output, which in turn facilitates larger-scale production methods.

This increase leads to what economists refer to as increasing returns to scale, where the addition of labor results in a disproportionately larger increase in output.

Russ Roberts: Now, let’s discuss Adam Smith’s insightful observation: “The division of labor is limited by the extent of the market.” Why is this significant?

Michael Munger: This concept ties back to our earlier discussions on markets as institutions that facilitate impersonal exchanges. The extent of the market is defined by the number of participants engaged in reducing transaction costs.

These institutions include legal frameworks that enforce property rights and contract laws, which ensure that promises are upheld. A well-functioning market requires both a desire for fairness and a legal system that supports it.

Russ Roberts: Expanding on that, a larger market allows for greater specialization and division of labor. The more individuals we can trade with, the more efficient our production becomes.

Michael Munger: Right. Returning to our four-person example, if we expand our trading network to include neighboring villages, we can significantly enhance our productivity. By specializing in agriculture and trading our surplus for fish, we can optimize resource allocation and increase overall wealth.

This dynamic illustrates how larger markets enable greater specialization, leading to increased output and prosperity.

Russ Roberts: The larger the trading pool, the more opportunities for specialization arise. This concept is vital because it means that as we engage with a broader market, we can leverage our skills more effectively.

Michael Munger: Precisely. In our earlier example, if we specialize in farming and trade our surplus with a coastal village that excels at fishing, we can achieve remarkable productivity gains through division of labor.

This process is further amplified when we consider technological advancements that arise from increased specialization, allowing us to scale up production significantly.

Russ Roberts: Consider the implications if you had a hundred highly skilled individuals on a resource-rich island. Despite their talents, they would struggle due to the limited capacity for specialization in a closed environment. In contrast, engaging with a global market of seven billion people allows for unimaginable specialization and prosperity.

Michael Munger: This leads us to what Deirdre McCloskey refers to as the Great Enrichment. Historically, we witnessed little improvement in living standards until the last couple of centuries. Now, a simultaneous rise in population and wealth reflects the power of markets and specialization.

The combination of population growth and increasing returns from division of labor has elevated overall well-being, illustrating that economic growth is not a zero-sum game.

Russ Roberts: Precisely. Many perceive wealth as a zero-sum game, but the reality is that economic advancement can occur without anyone losing ground. This fundamental shift in understanding is critical, as it highlights the potential for widespread prosperity.

Michael Munger: Indeed, Smith anticipated this phenomenon. While he may not have foreseen all the intricacies of modern capitalism, he understood that wealth arises from exchange, not merely from hoarding resources.

Russ Roberts: Let’s discuss capitalism itself. Until our recent conversation, I didn’t fully grasp its complexities. Can you elucidate what capitalism truly entails?

Michael Munger: To be frank, most people lack a clear understanding of capitalism. My definition may differ from conventional wisdom, but I see capitalism as an evolution of market mechanisms.

Russ Roberts: Please elaborate.

Michael Munger: Capitalism builds on the foundations of voluntary exchange and markets. It assumes that all exchanges and divisions of labor are functioning effectively. However, it also encompasses the institutions, attitudes, and cultural factors that support these systems.

Simply establishing a stock market does not create capitalism; it requires a societal framework that supports ethical behavior and trust in economic interactions.

Russ Roberts: So, what distinguishes capitalism?

Michael Munger: Capitalism introduces specialized market institutions that facilitate “time travel.” This concept addresses the challenge of developing fixed capital—assets that enhance productivity but are not easily converted back into liquid form for investment. The key term here is “liquidity.”

Liquidity enables investors to fund projects with the expectation of future profits, effectively allowing them to invest before realizing returns. This transformative aspect is crucial for economic development.

“`