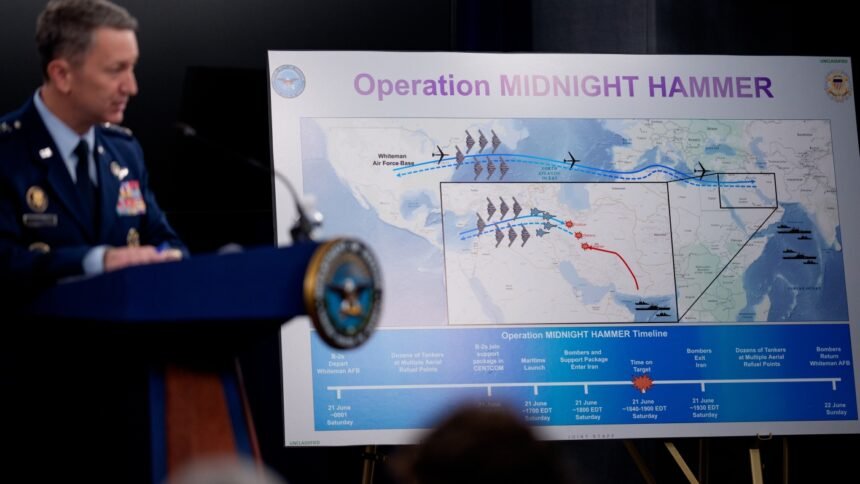

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Air Force Gen. Dan Caine discusses the mission details of a strike on Iran during a news conference at the Pentagon on June 22, 2025 in Arlington, Va.

Andrew Harnik/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Andrew Harnik/Getty Images

The framers of the U.S. Constitution lived in an age of muskets and messengers, when war moved slowly and left time for Congress and the president to confer. But by giving Congress the power to declare war and the president command of the military, they set the stage for lasting struggle over U.S. forces.

President Trump’s decision to launch airstrikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities without first consulting Congress has drawn sharp criticism from lawmakers who say the move bypasses their constitutional authority to declare war.

Speaking Monday on NPR’s Morning Edition, Sen. Mike Kelly, D-Ariz., said that while there’s little Democrats can do to force the administration to seek congressional approval, the president should still respect constitutional norms. “The administration should comply with the Constitution,” Kelly said. “Traditionally, presidents have done that. I know recently, sometimes with certain actions, when it is viewed as protecting the safety of our country, presidents can act, and then they should be able to notify us.”

Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., was more direct in his criticism. Appearing Sunday on CBS’ Face the Nation, he said: “The United States should not be in an offensive war against Iran without a vote of Congress. The Constitution is completely clear on it. And I am so disappointed that the president has acted so prematurely.”

So what does the Constitution actually say?

Article I gives Congress the power “to declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water.” Article II, meanwhile, designates the president as “Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States,” giving the executive authority to direct the military once conflict has been authorized.

“I think it’s pretty clear that the framers thought that any time we were going to be making the decision to go to war with another country, that was going to be a decision for Congress,” says Rebecca Ingber, a law professor at Cardozo Law School in New York.

Yet presidents have long sent U.S. forces into combat without a formal declaration of war. Stephen Griffin, a constitutional law professor at Tulane Law School, cites the Quasi War as an early example of the trend away from formal declarations of war between countries. This limited naval conflict between the U.S. and France at the end of the 18th century did not involve a formal declaration of war. Griffin notes that after World War II, advancements in military technology and the establishment of global institutions like the United Nations accelerated this trend. The creation of the atom bomb and the influence of the U.N. Charter shifted legal discussions towards concepts like “use of force” rather than formal declarations of war.

Griffin emphasizes that the Constitution does not require a formal declaration of war by Congress, but rather legislative approval such as an authorization for the use of military force (AUMF). He points to past conflicts like the Korean War, Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, and Kosovo crisis where formal declarations were not made, but military actions were authorized by Congress through different means.

Michael Glennon, a professor of constitutional and international law at Tufts University, highlights the War Powers Resolution of 1973 as a response to the imbalance of power between Congress and the president, especially in the aftermath of the Vietnam War. However, he notes that presidents have often ignored the resolution’s requirements, informing Congress rather than truly consulting them before military engagements. Despite this, there have been instances where the administration has complied with the resolution’s consultation requirements.

Even Secretary of Defense [Pete] Hegseth acknowledged that the administration is following the guidelines set forth in the War Powers Resolution. This demonstrates a level of respect for the resolution, which is widely believed to be constitutionally justified under Congress’ ‘necessary and proper’ power.

If the current attack on Iran is indeed a one-time occurrence, obtaining authorization from Congress for the use of military force may not be necessary. However, if the situation escalates into a back-and-forth conflict with Iran, President Trump should seek authorization. This would not only comply with the War Powers Resolution but also bolster his legal standing, as suggested by Griffin.